a DIACHRONIC study of the IMAGE of the POWERFUL FEMALE in POPULAR (and maybe other) CULTURES

Friday, December 19, 2014

YEAR 1965: HONEY WEST

While the Honey West novels are just tolerable time-killers, the short-lived 1965-66 teleseries remains a big step forward for shows featuring female protagonists. While this version of Honey was given a tough male companion in the form of Sam Bolt, he never hogged all the action as did the male companions of female serial-heroines like Nyoka. In all thirty episodes of the one-season series, Honey was invariably seen battling both male and female opponents with her masterful judo skills.

The scripts were light entertainment, but for all that much sprightlier than the BURKE'S LAW series on which ABC's version of the lady detective made her debut, as noted in detail here.

Perhaps the wittiest episode of the series was one entitled "The Fun-Fun Killer," in which Honey faced off against a bulletproof killer robot. And while to be sure, this robot turned out to be a human making a mechanical masquerade, I think it likely that the episode's scripters just might have remembered actress Anne Francis' prior encounter with a far more famous-- and genuine-- mechanical man.

Saturday, November 22, 2014

YEAR 1965: WONDER GIRL

As I noted in my essay on the first Wonder Girl, for some time I regarded the earlier character as one with the character who was essentially born in THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD #60 in 1965. But even though Bob Haney's script initially kept some continuity with the character from the WONDER WOMAN comic, any commonality was soon forgotten by both the writer and the readers of the TEEN TITANS feature.

In Haney's TITANS, Wonder Girl became her own character, strong and sassy, rather than a reflection of "Wonder Woman as a girl." Because this character was so dynamic, I suspect that few if any fans objected to the retconning in TEEN TITANS #22, where this Wonder Girl was revealed to be a mortal girl from man's world, who was taken in by Wonder Woman's Amazon sisters. given a boost from a miracle-making "purple ray" so that she too became a souped-up Amazon living on Paradise Isle. She also began using the everyday name "Donna Troy" as a salute to her mentor Princess Diana (the one with the lasso and the bracelets, that is). I guess "Troy" was chosen because it had a vaguely Greek-ish sound to it.

The second Wonder Girl's fame remained marginal in both the 1960s TEEN TITANS and a second iteration of it in the 1970s, though she made it into an animated TV series before Wonder Woman did, thanks to the Titans being adapted for segments of THE SUPERMAN/AQUAMAN ADVENTURE HOUR. However, thanks to her appearances in the 1980s series THE NEW TEEN TITANS, Wonder Girl's finally became a fan-favorite, thanks to her artistic depiction by George Perez and her characterization by Marv Wolfman, who had created her back-story in the 1960s story.

Sadly, due to the revisions of Wonder Woman series, the retcon-origin was no longer viable, since it depended on Wonder Woman and Paradise Isle having been known quantities in that narrative. After that, the poor girl was never the same. Over the ensuing years Wonder Girl would receive a dizzying number of reboots and retcons, to the point that I for one neither know nor care what she is these days-- much like another unfortunate victim of promiscuous rebootery, Marvel's hero The Falcon.

But when she was good-- she was very, very good.

Monday, October 6, 2014

YEAR 1964: THE SCARLET WITCH

Much like the Wasp and Marvel Girl, the Scarlet Witch received a bad rap, at least for her earliest depictions. Yet the character of Wanda couldn't be accused of any of the sins attributed to those Marvel characters. Maybe Wasp gushed about shopping and Marvel Girl was seen playing house-mother to the X-Men, but the Scarlet Witch was rarely if ever seen in such stereotypically feminine situations. And while one must admit that the previous two femmes were not that formidable, the Scarlet Witch's power-- to cause catastrophes just by pointing her hands-- was not so marginal. Nor could anyone argue that it was largely defensive in nature, as with the Invisible Girl's force fields. In one early appearance the Witch beats the Swordsman by causing a machine near him to explode, and in a later one, she causes the ground beneath a tank to collapse.

I've only encountered one rather vague criticism of the Scarlet Witch, possibly originating with Trina Robbins: the Witch was a heroine whose main power was to "pose and point." Maybe the criticism was that it placed the heroine on display for the evil male gaze, as opposed to having her engage in rough-and-tumble battles like the majority of Golden Age comics-heroines. Nevertheless, the central conception of the Scarlet Witch was that she was a mutant version of a witch, and the archetypal idea of a witch is that of a being who casts spells on others-- not a bare-knuckle fighter.

The worst one could say of the early Witch was that she didn't have much backstory, or much direction beyond choosing to fight evil as an Avenger. Of course, one could say the same of many of Marvel's male heroes in the 1960s: the Human Torch goes to college for a while, and then drops it to pursue his romantic interests-- which sounds like a stereotypically feminine thing to do. Arguably in the 1970s and thereafter, the Scarlet Witch eclipses the Torch and many others. Through her controversial romance with the android hero Vision, she showed a level of courage that surpassed the battles with super-villains, and she hopped up her powers through the study of witchcraft. This seems to have been her best period as a character, though I confess I have no idea what her status is these days.

Friday, September 19, 2014

YEAR 1963: MERA

Whereas Hawkgirl was created as an integral part of the Silver-Age HAWKMAN feature, Mera-- DC's first Silver-Age character to marry the hero of her feature-- seems to have come about by happy accident.

Arguably, the template from which she derives is not so much Hawkgirl, Lois Lane or Carol Ferris, but that of Superman's nemesis Mr. Mxyzptlk. Although Mxyzptlk remained a perpetual thorn in the side of the Man of Steel, it might be argued that he indirectly spawned a plethora of helpful imps who either regularly or irregularly assisted DC heroes. 1959's "Bat-Mite" was conceived in the vein of a pest who wanted to be helpful to Batman, but others were better helpmates, like "Cryll," a shape-shifting alien who started assisting Space Ranger regularly in 1958. The first issue of Aquaman's 1962 magazine introduced a helpful extra-dimensional imp, "Quisp," who was only made occasional appearances. Quisp would be phased out of the feature as soon as Mera appeared in issue #11, and not only did she take his position, she was also given, via editorial fiat, the same powers Quisp had displayed: the ability to manipulate water much as Green Lantern manipulated his ring's energy, turning water into solid, offensive objects like clubs, fists, or, as seen above, giant monsters.

Mera quickly became a dominant force in the feature, somewhat shoving Aqualad to one side. She married the titular King of the Seven Seas in issue #18, about a year after her debut, and gave the feature a more domestic feel, particularly when she gave birth to Aquaman's first son.

Mera's popularity, like that of many other Silver Age heroines, has waxed and waned many times. At present, she seems to have undergone a slight rebirth, thanks to the "Brightest Day" series. Not surprisingly, I find that she, like Star Sapphire, had her best stories in the Silver Age and never quite made a meaningfuil transition to the current era of DC Comics, as did characters like Batgirl and Black Canary.

Thursday, August 21, 2014

YEAR 1963: ELASTI-GIRL

A while back, ultimate fighter Ronda Rousey-- who made her film debut this month in EXPENDABLES 3-- called out comics "for being sexist." In her quote she sneers at Invisible Woman and Marvel Girl, and even finds a reason to downgrade Wonder Woman. It's a typically thoughtless celebrity quote, but a lot of full-fledged fans have made similar claims about the supposed marginalization of all female characters in the comic book medium. And though I've made some criticisms of the original Marvel Girl myself, Rousey's broad criticism sounds almost like it was derived from an almost identical oversimplification that appeared in Trina Robbins' THE GREAT WOMEN SUPERHEROES.

One of the many powerful heroines Robbins completely overlooks is the female member of the 1960s DOOM PATROL: Elasti-Girl. Perhaps she was overlooked precisely because she weakened Robbins' case re: marginalization. Like the other members of the team, the character was once an ordinary mortal who became "super" due to a cataclysmic event: after actress Rita Farr accidentally inhaled mysterious volcanic gases, she gained the power to grow to the size of a skyscraper or to shrink to the size of a mouse. The latter ability came in handy for the occasional espionage situation, but unsurprisingly Elasti-Girl spent most of her 1960s career "getting big." As the above panels show, the heroine could even enlarge discrete portions of her body at a given time.

Though her partners Robotman and Negative Man were both "heavy hitters" in their own right, Elasti-Girl was one of the first, if not the first, times that the female member was the "heaviest hitter" on the team. She and her fellow members perished in the DOOM PATROL's final issue, but her male compatriots were both revived in the 80s and 90s while Rita stayed dead. For all I know, she may have been revived in recent years, but I for one wouldn't mind if she'd been kept safely dead back in the period of her conception.

Wednesday, August 6, 2014

YEAR 1963: THE WASP

Many early 1960s Marvel heroines get a bum rap, but none more so than the Wasp.

She was introduced as a partner to the Ant-Man in TALES TO ASTONISH #44, the same issue in which the sketchy backstory of the main hero was given new depth. This story revealed that scientist Henry Pym lost his first wife to the Communist menace, and this later motivated him to devise his size-changing abilities in order to fight all forms of crime and tyranny, as the Ant-Man. But years later he met a potential replacement in heiress Janet Van Dyne, a much younger woman who returned his interest, albeit covertly.

However, in keeping with the slam-bang world of early superhero comics, no sooner did they meet than an alien monster killed Janet's father. She swore vengeance in the presence of Pym, so right away he revealed his costumed identity and invited her to become his crimefighting partner as the Wasp-- albeit with very different shape-changing powers, which extended to giving her Tinkerbelle-like wings in her miniature form.

Many fans have not liked the Wasp simply because she was not a powerhouse, and was often relegated to camp-following her partner-- who soon upgraded his powers as "Giant-Man"-- and as comedy relief. But these fans overlook that the Wasp was more than a source of woman-based jokes about going shopping and the like. The Pym-Van Dyne interaction was a bit like a famous quote explaining the appeal of the Astaire-Rogers team: "He gave her class, and she gave him sex appeal." Stuffy scientist Hank Pym didn't really have a lot of class to offer, but he did have scientific smarts and a sense of mission. Janet Van Dyne internalized many of those elements, but added her own very feminine take on all of the male alarums and emergencies. That's not to say that she invalidated those struggles, but she grounded them in a greater sense of everyday reality.

Over the years the Wasp received assorted power upgrades and became the Avengers chairman for a time. Currently she may be dead, though this probably won't last. Still, her original incarnation remains her best version; one that gave full reign to Stan Lee's phenomenal abilities to provide credible voices for a wide spectrum of comics-characters.

Thursday, July 24, 2014

YEAR 1962: STAR SAPPHIRE

Technically the character who became best-known for transforming into the DC character Star Sapphire appeared in 1959, not 1962. However, it's only in the latter identity that Carol Ferris, girlfriend of Green Lantern, concerns this blog.

I've already provided a detailed myth-analysis of the character's origins in this essay, so I won't tread the same ground again here. I neglected to mention that the name "Star Sapphire" originated in a Golden Age FLASH villainess, and that another character using the name briefly appeared in the 1970s title SECRET SOCIETY OF SUPER-VILLAINS. However, as far as impact goes, both of these figures are nugatory: Carol Ferris is the only Star Sapphire with any mythic resonance.

Unfortunately, much like many of the temporary super-forms Lois Lane assumed in the Superman titles, Carol's never quite became much more than a recurring problem for featured hero Green Lantern. The three stories that appeared in the 1960s-- authored by John Broome, Gardner Fox and Gil Kane-- represent the apex of the character's history.

In later DC comics, Star Sapphire went through a bewildering number of mutations. Sometimes she was a Jekyll not responsible for Hyde's crimes. Sometimes she was the very embodiment of the tyrannical female. She's certainly not the only character to have received such ambivalent treatment; arguably most characters who last a long time in corporate-owned comics-- including featured heroes-- suffer the same fate. But to date few of the attempts to re-define Star Sapphire have "taken." Even Steve Englehart, whose 1990s GREEN LANTERN series posited that the Zamarons were the female half of the all-male Guardians race-- was unable to give Star Sapphire a new lease on life. The character still appears, but her raison d'etre was in a sense left behind in the Silver Age.

As a minor side-note, though by the 1960s most fans had forgotten the Golden Age Star Sapphire, Robert Kanigher had not forgotten that he created her. In a late 1960s WONDER WOMAN scene, in which editor Kanigher was listing his accomplishments for the fans, he specified that he was the creator of "Star Sapphire"-- no doubt puzzling many of the readers who only knew of the Carol Ferris version.

Monday, June 23, 2014

YEAR 1961: HAWKGIRL

When comic-book historians complain about the lack of vivid heroines in the 1960s, they usually dismiss Hawkgirl as a mere shadow of her male partner-- not least because the franchise, debuting in THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD #34, was named "HAWKMAN." This could be fairly said of many "-girl" sidekicks, not least the Hawkgirl of the Golden Age-- but not Shayera Hol, wife of Katar. The premise established a strong sense of equality between the team-mates: both were accredited police officers of the alien world Thanagar, equally adept with advanced technology and good at battling evildoers. As to why Thanagarian cops tended to fly around with artificial wings and anti-gravity devices, Gardner Fox supplied the usual SF-rationales, which were of less importance than the kinetic pleasures of flying superheroes.

Unfortunately the HAWKMAN feature wasn't notably successful, and though the Hawks had a couple more short-lived series, as well as appearing in features like JUSTICE LEAGUE, this version of the franchise petered out with the introduction of DC's "Crisis" continuity, after which the characters were substantially revised. Thus the 1960s remains the height of Shayera Hol's fortunes, during which she rarely served as "hero's kidnapped sidekick." In fact, HAWKMAN #14 is devoted to the proposition that Hawkgirl gets to save her hubby from a man-stealing alien amazon named "Queen Alvit." Actions speak louder than words:

Wednesday, April 30, 2014

YEAR 1959: MALEFICENT

1959's SLEEPING BEAUTY may have been the first fantasy-film I saw on the big screen, since I have an intense memory of the end scenes-- Prince Philip's flight from Maleficent's castle with the help of the three fairies, and the climactic duel between the princess and the villainess in her dragon-form.

A number of elements in the Brothers Grimm story "Little Briar Rose" and its congeners had to be changed to please the ethos of the audience Walt Disney sought to please. Even as a kid, I noticed that one substantial change: that the "sleeping beauty" of the title doesn't really sleep very long, any more than the rest of the court within the enchanted castle. This change certainly came about because Disney's adapters wanted Princess Aurora to "meet cute" with Prince Philip. Were they worried about the inappropriateness of a princess marrying up with the first fellow who came along and kissed her into wakefulness? In addition, the thorn forest that grows up around the castle isn't put there by a good fairy, seeking to protect the castle for centuries until the destined prince comes along: the thorns are just a last-minute defense by Maleficent, sent to delay Philip. They certainly add to the colorful background of the climax but don't serve any narrative purpose.

In the Grimms' version, one of the thirteen fairies is simply excluded from Briar Rose's christening because the king and queen don't have enough plates for all of them. OK, little hard to believe, given that they're ROYALTY, but then, how often do folktales focus on detailed motivation? The excluded thirteenth fairy curses Briar Rose and has her curse mitigated by the twelfth fairy. After that, the thirteenth fairy is never seen again, though in some tellings Briar Rose has a later encounter with another villainess, an Ogre Queen to whom her prince is related.

Obviously a feature film needed a more prominent villain, one who could be punished at the conclusion for having visited such an evil fate on a helpless victim. In the film Maleficent is excluded because she's just plain evil, and she justifies her reputation with her curse and her subsequent attempts to bedevil Aurora. The character's design is plainly intended to give her a resemblance to the Christian Satan, a visual reference followed up literally in the climax, when Maleficent confronts Philip, claiming to unleash on him "all the powers of hell." It's a neat mythic touch that she chooses to change into a dragon to fight the prince, since Revelation in the New Testament equates Satan with "the great dragon."

Maleficent was killed dead at the end of SLEEPING BEAUTY, and I prefer to remember her that way, taking no notice of any later "revivals."

Wednesday, April 23, 2014

YEAR 1959: WONDER GIRL

There was a time when I tended to disregard the first version of Wonder Girl in favor of the altered version who became a member of DC's TEEN TITANS title. More recently, though, I've decided that the original character definitely occupies a distinct place in the history of femmes formidables.

In essence one could argue that her template was borrowed from that of Superboy: if you have a young audience that's willing to buy adventures of an adult hero/heroine, maybe the same audience will also buy a teen version of same, closer in age to said audience. Unlike DC's Superboy, the teen version of Wonder Woman never sustained her own feature: her stories always appeared in issues of WONDER WOMAN. Sometimes "Wonder Girl" stories shared space in the magazine with "Wonder Woman" stories. Sometimes stories of Wonder Girl, living on Paradise Isle at a time when she had yet to embark on her crimefighting mission, took over the whole book. Eventually editor/writer Robert Kanigher must have decided that Wonder Girl stories might have more currency if she could appear in man's world at the same time that Wonder Woman existed. Therefore the scientists of Paradise Isle came up with a magical machine that allowed the teenaged heroine to occupy the same time as her adult version-- not to mention a "toddler" version, "Wonder Tot," about whom the less said, the better.

I've sometimes wondered why Kanigher chose to emphasize the Wonder Girl version of the main heroine for so many years, giving up only near the end of his tenure on the title. Kanigher had edited the WONDER WOMAN title since 1946 and became its exclusive writer in the following year. In 1958 the original artist H.G. Peter left the book-- whether at someone's behest or not, I do not know-- and the title's most regularly-employed artists were the penciller-inker team of Ross Andru and Mike Espositio. In issue #98 Kanigher and the new artists broke all ties with the Marston-Peter version of the character and formulated a new origin in which the Amazons were the wives of warriors killed in battle and Princess Diana was born naturally of man and woman, receiving her great powers via the blessings of the gods, much after the fashion of the Sleeping Beauty folktale. Eight issues later, Kanigher introduced Wonder Girl, and kept her on a regularly appearing alternative to the titular heroine.

It's likely that the sales of WONDER WOMAN had slipped during that period, prompting the creators to try different strategies to pump up sales. At the same time, for professional comics-creators the important thing was to produce material efficiently, to meet the ever-steady demand of commercial comic books. Interestingly, during the 1950s Kanigher was less known for his work with superheroes than with war comics:

Starting in 1952, Kanigher began editing and writing the "big five" DC Comics' war titles: G.I. Combat, Our Army at War, Our Fighting Forces, All-American Men of War, and Star Spangled War Stories.[9][10] His creation of Sgt. Rock with Joe Kubert is considered one of his most memorable contributions to the medium-- Wiki page on Robert Kanigher.

A lot of Kanigher's Wonder Girl stories resemble the stock war-stories motif of the "green recruit;" the guy who doesn't yet know how to conduct himself in combat situations but who over time develops the requisite skills. Thus Wonder Girl allowed Kanigher to re-use favorite tropes from his war books, to maximize his productivity.

In terms of quality the WONDER GIRL stories are largely of a piece with those of WONDER WOMAN: the daffy, make-it-up-as-you-go-along aspects of the stories is moderately entertaining, but rarely compelling. Kanigher never pushed himself on this title, with the result that every story reads pretty much like every other one. Wonder Girl's tales were usually a bit less overtly violent than Wonder Woman's, so Wonder Girl's feats were usually less about defeating villains and more about outmaneuvering beasts and monsters, like her duel with the shark in the Irwin Hasen cover above. On the plus side, though, she and Supergirl were the only two teen superheroines that female readers of the period might have enjoyed, though on the whole Supergirl's adventures were better written. So Wonder Girl does hold a definite niche in "formidable history," though it's a place largely superseded by the independent version of the character developed in the TEEN TITANS continuity.

Tuesday, April 1, 2014

YEAR 1957: HONEY WEST

As of this writing I've only read three of the eleven novels starring Honey West, one of the best-known female detectives of the 20th century, though her fame may derive from the one-season 1965-66 teleseries, featuring a very different version of the character.

The first three novels, collected as THE HONEY WEST FILES vol. 1, are breezy entertainments clearly aimed, despite their feminine star, at a male audience. Most of the writing by pseudonymous author "G.G. Fickling" was by one Forrest Fickling, though he got some collaborative aid from his wife Gloria. The titular Honey, like many heroes of both genders, gets into her dangerous business because her father is killed by criminals. She has no regular assistants, in contrast to the teleseries, but if the rest of the novels are like these three, readers weren't regularly picking up copies to see Honey trounce thugs with judo tosses. There are a few such scenes here and there, but-- in keeping with the target audience-- there are a lot more scenes in which Honey finds herself ogled and/or groped by a half-dozen males of varying quality in each story. Her character pretty much accepts this as the way of the world, but she does have a knack for the basic putdown and defends herself as well with words as with judo.

All that said, Honey does have brains as well as beauty, and she does solve her cases with some decent if far from exceptional detective-work. This might go toward explaining the less frequent use of violence; in contrast to the novels of Mickey Spillane, the Honey West stories are pretty firmly in the groove of the ratiocinative detective tale.

Friday, March 14, 2014

COVERFEMMES #2

The aforementioned book also overlooks a lot of the significant starring or co-starring femmes of the Silver Age, such as:

MERA

ELASTI-GIRL OF THE DOOM PATROL

And, as I've pointed out elsewhere, MADEMOISELLE MARIE, who actually became the cover feature to DC's STAR-SPANGLED WAR STORIES, at a time when Supergirl only had a backup.

MERA

ELASTI-GIRL OF THE DOOM PATROL

And, as I've pointed out elsewhere, MADEMOISELLE MARIE, who actually became the cover feature to DC's STAR-SPANGLED WAR STORIES, at a time when Supergirl only had a backup.

YEAR 1957: KYRA ZELAS

I confess that I haven't seen the 1957 SHE-DEVIL in over 20 years, and haven't found even a greymarket source for a copy. Thus I won't review the film here, but I will link to this review at DVD Savant.

This seems to be the ultimate-- in the sense of "the last"-- adaptation of Stanley Weinbaum's short story, "The Adaptive Ultimate." I suspect that the short story's appeal to film, radio and television may have been that its "monster" was simply a woman who changed from less-than-attractive to a bombshell, in this case played by popular B-actress Mari Blanchard. The fact that the monster needed no more than a basic Hollywood makeup job probably made it attractive to producers than its loose adaptation of Stevenson's "Jekyll and Hyde" trope. Still, SHE-DEVIL does deserve to be known as one example of the comparative wealth of femmes formidable- films that appeared during the 1950s decade.

One interesting addition to the standard adaptation of "Adaptive" is a memorable scene in which Kyra, having married a wealthy man, simply does away with him by crashing their car. Her powers enable her to survive the wreck while he perishes, while the apparent circumstances give her a great murder-alibi. Amusingly, the footage of the car-crash was lifted from an earlier femme formidable film of the period, 1952's ANGEL FACE.

Thursday, March 13, 2014

COVERFEMMES #1

This is a new feature I'm adding, one that may supplement the ongoing-- but infrequently updated-- "diachronic study."

I'd seen Louise Simonson's DC COVERGIRLS on stands when it was new but wasn't too impressed with most of the choices. I freely admit that this may be nostalgia on my part, as I prefer the comics covers of my youth to many-- though not all-- of those published today.

The other week I picked up a cheap copy of the book, and once I had a clear idea of everything it covered, I decided to touch on some of those "better covers" featuring "femmes" of some sort, though not invariably "formidable" types.

In the original version of this blog, I devoted some posts to some of these, including:

The second SUPERGIRL

The first SUPERGIRL and the third BATGIRL combined:

The first BATWOMAN

One of the two best Golden Age CATWOMAN covers

KNOCKOUT

THE LEGION

STAR SAPPHIRE

THE GOLDEN GLIDER

Now, these are only the best DC covers that I've reproduced so far; a really good survey of "girls on covers" would have to include all companies. So whenever I update this feature, I'll take a stab at some of DC's competitors as well.

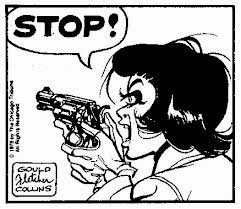

And just to prove that I don't necessarily have to confine myself to pulchritudinous pictures, here's a cover featuring a "dominant female" that I certainly HOPE no one finds sexy.

I'd seen Louise Simonson's DC COVERGIRLS on stands when it was new but wasn't too impressed with most of the choices. I freely admit that this may be nostalgia on my part, as I prefer the comics covers of my youth to many-- though not all-- of those published today.

The other week I picked up a cheap copy of the book, and once I had a clear idea of everything it covered, I decided to touch on some of those "better covers" featuring "femmes" of some sort, though not invariably "formidable" types.

In the original version of this blog, I devoted some posts to some of these, including:

The second SUPERGIRL

The first SUPERGIRL and the third BATGIRL combined:

The first BATWOMAN

One of the two best Golden Age CATWOMAN covers

KNOCKOUT

THE LEGION

STAR SAPPHIRE

THE GOLDEN GLIDER

Now, these are only the best DC covers that I've reproduced so far; a really good survey of "girls on covers" would have to include all companies. So whenever I update this feature, I'll take a stab at some of DC's competitors as well.

And just to prove that I don't necessarily have to confine myself to pulchritudinous pictures, here's a cover featuring a "dominant female" that I certainly HOPE no one finds sexy.

Wednesday, March 12, 2014

YEAR 1956: THE SWAMP WOMEN

For some reason various sources list this Roger Corman "roughie" as appearing in either 1955 or 1956, but the most reliable sources seem to go with the latter date.

Though this is far from the worst film ever to be spoofed on MST3K, SWAMP WOMEN provided one of the comedy-team's best riffs, in part because it's one of Corman's dullest films. It's one of three films Corman completed in or around 1956 with actress Beverly Garland, but both have greater moxie than this one. GUNSLINGER, featuring Garland as a tough lady sheriff, deserves to have its own entry here, while IT CONQUERED THE WORLD has earned a place on many viewers' "best bad SF film" lists.

SWAMP WOMEN, though, is basically a "fugitive on the run" story, with the comparative novelty that the fugitives are four gun-molls escaped from a women's prison. One among them, name of Lee Hampton, is in truth an undercover policewoman who arranges the escape so that the real gun-molls will cut her in on a cache of stolen diamonds. Her brilliant scheme doesn't make a lot of sense in that she apparently has no means of calling for backup. Maybe she assumed she was tough enough to take down all three molls in the wilds of the Louisiana swamp?

To her good fortune, during the escape the Swamp Women come across a rich young guy named Bob (Mike Connors), his good-time girl date, and the guy piloting their canoe. The bad girls want the canoe, so they kill the pilot, and eventually the good-time girl too, despite Lee's attempt to prevent bloodshed without blowing her cover.

This leads to the only mild asset of the film: a G-rated kinkiness as the four comely women all take turns mooning over the safely-trussed-up Bob. In addition, Corman-- who may have noticed an increase in female-centric exploitation flicks of the decade-- appears to be playing to the catfight-connoisseurs in the audience, just as GUNSLINGER did. But whereas GUNSLINGER's simple characters are involving, the script's idea of "characterization" is to have the molls sitting around dreaming of the ways they'll continue flouting the law after they cash in on the diamonds.

To be sure, "real molls" Marie Windsor, Beverly Garland, and Jill Jarmyn do pretty well with their threadbare roles, though for most viewers their fistfights will prove more memorable than their line-readings. Eventually Bob and Lee team up to defeat the real molls and the law recovers the stolen diamonds-- a dull resolution that may have persuaded Corman to give more attention to the outlaws in some of his future endeavors, like 1957's NAKED PARADISE and 1958's MACHINE GUN KELLY.

Monday, March 3, 2014

YEAR 1955: POLICEWOMAN LIZZ

I can't top author Jay Maeder's observation from his DICK TRACY: THE OFFICIAL BIOGRAPHY on the subject of Lizz's introduction. She was not just the first policewoman to become a regular fixture in the Dick Tracy strip, but also an indicator of author Chester Gould's awareness of changes in the air.

Lizz (whose married surname was "Worthington," though it wasn't regularly used) first appeared in 1955. She began as a nightclub photographer whose husband was killed by petty leather-jacketed hoodlum Joe Period. Period was an unmistakable clone of Marlon Brando's character from 1953's THE WILD ONE, but cast as an unmitigated lowlife. The Joe Period arc, ending with the villain's capture, concluded after a few months, but this swaggering embodiment of 1950s "edge" didn't come back. Lizz, however, was inspired to become a policewoman by Dick Tracy's example, and she remained a regular supporting character throughout the remainder of Gould's tenure and continued to appear regularly thereafter. Gould created many one-shot characters, and Lizz easily could have been one of these. The fact that she stayed around, even in the years prior to the development of "second-wave feminism," suggests to me that Gould valued, either personally or professionally, the representation of women in the police force.

Admittedly, Lizz is not a great femme formidable in the mold of Gould's villainesses, particularly Breathless Mahoney. But she was consistently represented as a tough customer, skilled both in judo and firearms. Oddly, since she was first introduced as an adversary to a "fifties rocker," she was later married to a sort of "hippie cop" with the painful name of "Groovy Grove." But Grove disappeared from the strip, and Lizz remained-- again, rarely if ever using her married name.

Sunday, February 16, 2014

YEAR 1954: ANNIE OAKLEY

There was of course no resemblance between the real-life sharpshooter Annie Oakley and this early television heroine, played by frequent Gene Autry leading lady Gail Davis.

I've only seen a couple of episodes of this now-obscure western series. From these few, I can still tell that though Davis's pigtailed Annie character wasn't stridently feminist, she made no bones about being a better shot than any man in her small town of Diablo, Arizona.

Though the show isn't of easy access today, it had a definite impact on the female audience of the 1950s. Ms. Davis is quoted as saying:

"Back then I knew the show was having a positive impact, especially on little girls. It wasn't until years later that I realized just how much. Little girls had turned into influential women, thanking my portrayal of Annie for showing them the way."

YEAR 1953: LORNA THE JUNGLE GIRL

Prior to Atlas Comics' debut of JANN OF THE JUNGLE, writer Don Rico and artist Werner Roth conceived one of the better jungle girls of the comics-medium: Lorna, usually known as "the Jungle Girl" though technically her earliest tagline was "Jungle Queen."

In contrast to Jann, who was pretty much a cookie-cutter imitation of every other Sheena-imitation that had come down the pike, Rico's scripts for LORNA were usually literate. That's not to say that they were sophisticated: Lorna still ran into the usual menaces every other jungle-hero did: evil witch-doctors, prehistoric beasts, foreign spies and treasure-hunters. But though at this time the feminist movement was still far from influential on the body politic, Lorna did prefigure the feminist desire to puncture masculinist priorities.

I've mentioned that Sheena was one of the toughest representatives of the genre she founded in the comics-medium. Lorna could be tough, but as seen in the excerpt above, she was equally adept at skewering the male ego of her beloved, jungle-guide Greg Knight. Whereas Sheena's mate Bob was just a marginal figure, whom Sheena generally overshadowed, Knight actively preached to Lorna that the jungle was no place for a woman-- despite the fact that she was much better at slaying wild beasts than he ever was.

That said, she loved him, and frequently tried to please him, up to a point. She would mock him by calling him "my lord and master," but in the 26 issues of the LORNA comic, she never managed to convince him that she was his equal, much less his superior. Nevertheless, Knight was clearly the butt of the series' humor, for all that he was your typical "man's man." While LORNA was not precisely a satire of the jungle-adventure genre in comics, its light-hearted approach marks it as a superior example of same.

Saturday, January 25, 2014

YEAR 1949: KYRA ZELAS

The Stanley G. Weinbaum short story was adapted once for radio and three times for television. As I'm not dealing with radio productions on this blog, there's nothing I can say about the first television adaptation on STUDIO ONE because, as this reference notes, the original is "lost forever."

Versions of Weinbaum's story later appeared on the low-budget anthology serials TALES OF TOMORROW and SCIENCE FICTION THEATER, but as I recall, neither of these were particularly noteworthy. The short story's peculiar use of science and translation of the Frankenstein theme into the sexual-fantasy sphere comes across somewhat better in the 1957 film adaptation SHE-DEVIL, but not by very much.

Friday, January 24, 2014

YEAR 1948: POWDER POUF

Eisner's fierce femme formidable, Powder Pouf, only appeared in a couple of Will Eisner SPIRIT stories. She's not a great favorite among SPIRIT fans, lacking the tragic dimensions of SILK SATIN or the lovable larceny of P'GELL.

Her most noteworthy quality might be her violence. Whereas most SPIRIT femmes tended to beguile hapless males with their beauty, Powder Pouf is first seen robbing a shopkeeper by punching him, kicking him, and banging his head on pavement. Why she felt this necessary-- given that she was packing heat-- may never be known. When an ex-con named Bleaker Moore happened by, she used her gun to force him to be her accomplice. The Spirit tracked Powder down and kept Bleak from doing any more time.

Since the only other Powder story appeared a few months after the first, and again featured her interaction with sad-sack Bleaker, it would seem that Eisner had little in mind for her but a standard "tough girl." Bleaker, by contrast, appeared in a few more stories, so he may have been the real character Eisner sought to integrate into the Spirit's adventures.

YEAR 1947: DARNA

To be sure, the Mars Ravelo/Nestor Redondo superheroine who originally appeared in a 1947 issue of the Phillippines BULAKLAK MAGAZINE was called "Varga."

Only three years later did Ravelo succeed in relaunching the character under her best-known name, "Darna." As my only experience of Darna is having seen the 1991 film, I can only generalize that the character's origin seems to have been the same under both names. A white stone falls to Earth and is swallowed by young "Narda," who finds that she can then transform into a super-strong, near-invulnerable crimefighting warrior-woman.

Though Ravelo encountered considerable resistance to his character's publication-- he claimed to have conceived it in late 1939, just before World War II-- Darna has gone on to be something of a perennial figure in Filipino popular entertainment. Though some might assume that Darna was a copy of Wonder Woman, the character doesn't seem to have any of the Amazon's abstruse qualities. If anything, her transformation scene seems strongly indebted to the Golden Age Captain Marvel, who appeared in early 1940. Wikipedia observes that had Darna been published when Ravelo claims that he conceived her, she would have preceded Wonder Woman by one-and-a-half years-- though one may assume that such a Darna would have started out almost purely in the tradition of Siegel and Shuster's SUPERMAN.

Only three years later did Ravelo succeed in relaunching the character under her best-known name, "Darna." As my only experience of Darna is having seen the 1991 film, I can only generalize that the character's origin seems to have been the same under both names. A white stone falls to Earth and is swallowed by young "Narda," who finds that she can then transform into a super-strong, near-invulnerable crimefighting warrior-woman.

Though Ravelo encountered considerable resistance to his character's publication-- he claimed to have conceived it in late 1939, just before World War II-- Darna has gone on to be something of a perennial figure in Filipino popular entertainment. Though some might assume that Darna was a copy of Wonder Woman, the character doesn't seem to have any of the Amazon's abstruse qualities. If anything, her transformation scene seems strongly indebted to the Golden Age Captain Marvel, who appeared in early 1940. Wikipedia observes that had Darna been published when Ravelo claims that he conceived her, she would have preceded Wonder Woman by one-and-a-half years-- though one may assume that such a Darna would have started out almost purely in the tradition of Siegel and Shuster's SUPERMAN.

Sunday, January 12, 2014

YEAR 1947: THE THORN

The Thorn, unlike many of the super-villains of late 1940s DC, was not revived in the Silver Age, but had to wait until the Bronze Age. Even then, she was revived not so much to give her time in the super-villain spotlight, but to retcon her as the mother of two new superheroes.

Created by writer Robert Kanigher and artist Joe Kubert in FLASH COMICS #89, the Thorn is distinguished for being one of the few "Jekyll-Hyde" villains during this period. In her first appearance, the green-clad villainess showed up to challenge the Flash on his own turf. Thorn carried a small arsenal of thorns that could explode or prick flesh, and she apparently made use of the latter whenever she whirled in place like a dervish, making it impossible for the Flash to lay hands on her. No sooner does the Thorn escape the hero than he meets a woman named Rose, who claims to be the villainess' beneficent blonde sister, hunting Thorn in order to forestall her evil career. Rose relates to Flash a complicated tale as to how she and her sister came to have opposing natures, thanks to the assignments given them by their botanical mentor Dr. Hollis.

Though the story telegraphs the expectation that the two entities are one, even before the Big Reveal, but I find it fascinating that Rose's phony stoty situates Hollis as a rather arbitrary father-figure who allots a pleasant task to one sister, and a grueling, unpleasant one to the other-- though significantly, the evil version of Rose says that she doesn't "mind the hurt." Presumably the second and last Golden Age story-- which I have not read-- reveals the real sequence of events, but the phantom of an arbitrary father-figure is significant nonetheless.

The entire first story appears here on Pappy's Golden Age Blogzine. In 1970, Robert Kanigher would recycle two aspects of this villain-- her schizophrenic double identity and her weaponized thorns-- into his heroic "Thorn" character, Rose Forrest.

Created by writer Robert Kanigher and artist Joe Kubert in FLASH COMICS #89, the Thorn is distinguished for being one of the few "Jekyll-Hyde" villains during this period. In her first appearance, the green-clad villainess showed up to challenge the Flash on his own turf. Thorn carried a small arsenal of thorns that could explode or prick flesh, and she apparently made use of the latter whenever she whirled in place like a dervish, making it impossible for the Flash to lay hands on her. No sooner does the Thorn escape the hero than he meets a woman named Rose, who claims to be the villainess' beneficent blonde sister, hunting Thorn in order to forestall her evil career. Rose relates to Flash a complicated tale as to how she and her sister came to have opposing natures, thanks to the assignments given them by their botanical mentor Dr. Hollis.

Though the story telegraphs the expectation that the two entities are one, even before the Big Reveal, but I find it fascinating that Rose's phony stoty situates Hollis as a rather arbitrary father-figure who allots a pleasant task to one sister, and a grueling, unpleasant one to the other-- though significantly, the evil version of Rose says that she doesn't "mind the hurt." Presumably the second and last Golden Age story-- which I have not read-- reveals the real sequence of events, but the phantom of an arbitrary father-figure is significant nonetheless.

The entire first story appears here on Pappy's Golden Age Blogzine. In 1970, Robert Kanigher would recycle two aspects of this villain-- her schizophrenic double identity and her weaponized thorns-- into his heroic "Thorn" character, Rose Forrest.