Sunday, December 30, 2012

YEAR 2002: ALICE (RESIDENT EVIL)

Lara Croft remains the best known action-heroine created for an American videogame. However, the zombie-killing game RESIDENT EVIL has one superior distinction: that it spawned the most financially successful film-series to come out of a game-franchise. Five Resident Evil films have come out as of this date, and all have starred the heroine created for the first film, the zombie-fighter Alice, consistently played by Milla Jovovich.

Following BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER it became more common for monster-fighters to be more than a little monstrous themselves. Alice begins her heroine-career as an employee of the Umbrella Corporation, an institution responsible for unleashing a plague of zombies upon the world. Alice turns against the Corporation and attempts to help ordinary people menaced by the subhuman creatures. She's originally just a highly skilled mortal but exposure to the zombie-virus enhances her strength and skills to phenomenal levels, at least in some of the movies.

Most of the other characters, whether continuing presences or one-shot types, are largely forgettable, so Alice would seem to be the character responsible for selling the film-series to its fans.

Labels:

alice (resident evil),

heroine headcount,

year 2002

YEAR 2001: PRINCESS YUKI

THE PRINCESS BLADE was a one-shot take on the 1970s manga-series LADY SNOWBLOOD, albeit transplanted to a vague post-apocalyptic environment.

Princess Yuki is the number-one swordswoman of a clan of assassins that serves an oppressive future government. In contrast to SNOWBLOOD she isn't initially motivated to avenge her mother's mother, but takes arms against the tyrants belatedly after she learns that they were responsible for said murder.

In contrast to SNOWBLOOD the movie doesn't attempt to evoke the poetic contrasts of the cold-hearted but warm-bodied assassin. But the swordplay choreography by Donnie Yen is better than average.

Saturday, December 29, 2012

YEAR 2000: MAX GUEVARA

DARK ANGEL, a two-season wonder produced by James Cameron, took place in a slightly dystopic future not very different from the present. Main character Max Guevara (Jessica Alba) was a genetically engineered super-soldier who escaped government confinement and attempted to blend with regular humanity, taking the job of a bicycle messenger. But not only does she have to dodge agency hunters, she gets embroiled in freedom-fighting by her mentor/lover, a cyber-journalist named Logan. To further complicate things, other super-soldiers, as well as beast-human hybrids called transgenics, manage to congregate in the same city where Max hangs her hat.

Cameron's future-world shows little original thought, but the fight-scenes are pretty kickass, frequently showing lean but super-strong Jessica Alba slamming around men twice her size.

As a side-note, I have to say that Alba is one of the few actresses who got worse the more experience she got, as witness her work in MACHETE next to this series.

Labels:

fibbers,

heroine headcount,

max guevara,

year 2000

Thursday, December 27, 2012

YEAR 1999: BATGIRL

Though the Barbara Gordon Batgirl remains the best known to the general public, Cassandra Cain is on the whole a more original transformation of the "female Batman assistant" concept.

In keeping with the darker spirit of comic books in the 1990s-- as well as her surname, modeled on that of the first person (according to the Bible) who committed a murder-- Cassandra begins with a stain on her soul, in contrast to the many simon-pure heroes of the Golden and Silver Ages. Long before becoming Batgirl, young Cassandra-- the child of assassins Lady Shiva and David Cain-- is trained to become an assassin herself. Not knowing any better, she does kill a victim, only to have such a negative reaction as to flee the influence of her father. She later finds sanctuary and re-training with the Batman Family, and adopts the name "Batgirl" with the blessing of Barbara Gordon. She later lost the title to another claimant, and then to a renascent Gordon-Batgirl.

The scripts, initially by Kelly Puckett, were fairly complex but I personally did not take to the manga-influenced art of co-creator Damion Scott.

Sunday, December 16, 2012

YEAR 1998: FAITH

In a general sense Faith is to Buffy the Vampire Slayer as Callisto is to Xena. However, the approach of the two teleseries to the idea of the "negative counterpart" couldn't be more different.

In XENA, Callisto makes her appearance within the teleseries' first season, while Faith doesn't show up until the third season of BUFFY-- though, to be sure, the show's first season was short, being that it was a midseason replacement.

Nevertheless, Callisto is conceived as a rebuke to Xena's attempt to make restitution for her past acts; she's a victim who chooses to turn villain in order to undo Xena's attempts at heroism. Faith is more like the "cool girl" who undermines Buffy's position as the center of her homebuddies' attention.

That said, by not being as thematically opposed to the series-heroine, Faith proves more malleable, going back and forth from hero to villain to hero again, and serves a major plot-function for the series as a whole by demonstrating that more than one Slayer can exist at a given time, as against the received Slayer mythology.

But perhaps her best quality is that the actress Eliza Dushku looked way better kicking vampire ass than Sarah Michelle Gellar did. Wikipedia reports that Dushku was offered a shot at a Faith teleseries, and that she passed on the concept. Given the reception of her later teleserials TRU CALLING and DOLLHOUSE, this might not have been the best decision.

Sunday, December 9, 2012

YEAR 1997: BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER

The 1992 BUFFY film remains important purely as a dry run for the more ambitious teleseries. Had Joss Whedon and his company not managed to find a new direction for the series-- merging horror, adventure, and enough motormouthed, self-referential dialogue to make Quentin Tarantino gag-- the film might scarcely be remembered any better than the Cyndi Lauper vehicle VIBES.

I noted in my XENA essay that I didn't think the "vampire slayer" mythos was quite as ambitious as the "warrior princess" concept. Nevertheless, both teleserials excelled in terms of portraying a relatively unexplored field: the dark side of the heroic femme formidable. Evil "femmes fatales" were as common as dirt in the history of pop culture, but heroines in the adventure tradition generally had to be simon-pure "good girls." Xena and Buffy were both noble souls who occasionally allowed rage or egotism to master them, as pop-fiction readers regularly saw with male heroes ranging from Batman to Mike Hammer.

The most intriguing aspect of Joss Whedon's mythos was that it was fundamentally atheistic despite the presence of multifarous demons. However, Whedon rarely explored this theme in depth in BUFFY as he would in ANGEL. Still, BUFFY was important in terms of Whedon forging his method of the brooding-loner-with-a-posse-of-faithful-friends-- not to mention the mass appeal of BUFFY's "take back the night" feminist theme.

Thursday, December 6, 2012

YEAR 1996: CALLISTO

Within the first year of the teleseries XENA WARRIOR PRINCESS, the producers came up with a yin to Xena's yang: Callisto, vengeance-driven warrior-maiden.

In so doing Callisto's creators followed a pattern not unlike those seen with classic comics-heroes. If Superman's power is brain, give him a mortal enemy who's all brain. If Batman's tightly wound, give him a lunatic clown as a nemesis.

In part Callisto-- referred to as "the psycho Barbie" by some pundits-- follows the Batman pattern. Because Xena's entire raison d'etre revolves around doing good in restitution for her past evil acts, Callisto makes the perfect counterpoint given that she's a victim of one of those evil acts, but one who refuses to grant Xena any forgiveness.

And in addition to being just as skilled in "Greek kung-fu" as is the heroine, she's Joker-crazy as against Xena's sober-sided toughness.

Unlike the Joker, the producers apparently wanted Callisto to complete a decisive character-arc, rather than being a routine sparring-partner. This proved a wise decision, resulting in a strong dramatic sequence-- ironically not on XENA but on the companion-show HERCULES-- in which Callisto has a time-traveling experience which roughly puts her in Xena's sandals, so to speak.

Further, Callisto finally does achieve an appropriate revenge upon her enemy, but in keeping with the philosophical sensibilities of the writers, it brings her no satisfaction. Having reached that apogee, the character only appeared a few more times in an altered form (as a kind of angelic presence) before the series concluded.

Saturday, November 24, 2012

YEAR 1995: XENA WARRIOR PRINCESS

Buffy the Vampire Slayer got out of the gate first and maintained popular in comic books some time after the demise of her television series. Despite that, Xena-- who premiered on an episode of HERCULES: THE LEGENDARY JOURNEYS before gaining her own series the same year-- is arguably the more ambitious femme formidable.

To say "ambitious" is not to portray the teleseries as something artsy and high-falutin'. XENA the series borrowed from a variety of popular sources-- sword-and-sandal movies, Hong Kong kung-fu films, dungeons-and-dragons and even westerns. Nevertheless, the writers were gutsy enough to simulatenously swipe from highbrow works like Greek epic and the Bible or from philosophers like Schopenhauer, resulting in a unique blend of the "high" and "low" that BUFFY can't quite match.

The theme of the warrior trying to turn his/her deadly skills to good ends is a favorite American theme, but the creators of XENA upped the ante. XENA episodes often concern the necessity for characters to "let go" of the lust for hate or vengeance -- and not only the villains. Both Xena and her sidekick Gabrielle frequently have to practice what they preach, and they don't always do so successfully. The Schopenhauerean ideal of relinquishing the will plays better than it lives.

Not to mention that in addition to all this philosophical complexity, Xena also had better fight-choreography than Buffy--

AND--

A better all-musical episode.

Monday, November 19, 2012

YEAR 1994: KAHLAN AMNELL

I haven't featured many characters as yet from the genre of prose fantasy, but I would remiss not to mention one of the better ones of the 1990s, Kahlan Amnell from Terry Goodkind's SWORD OF TRUTH series.

However, for the time being, this will have to be something of a placeholder, since I confess I've only read the first in Goodkind's multi-book series. I can provide no overall perspective as to how the character of Kahlan develops over the course of the series. Like many fantasy-fans I've seen the LEGEND OF THE SEEKER teleseries, but as this changes up the events of the books, this can hardly be a resource.

I might go out on a limb and say that Kahlan is notable for being an equal partner to the male hero in the course of the series, and that her particular power as a "Mother Confessor" is integral to Goodkind's take on magical power in his fantasy-sphere.

To top it off, I quote from the Sword of Truth Wiki:

"Outside of the Sword of Truth universe, Terry Goodkind reports that Kahlan was the first character he thought of, and that her iconic scene running from the D'Haran quad sparked the entire series."

Sunday, November 11, 2012

YEAR 1993: LOIS LANE

From the late 1960s on, the comic book Lois Lane had become noticably tougher, often if not consistently capable of taking out gunmen with karate chops. But the Lois Lane seen in both live-action and animated television shows was nearly incapable of self-defense. The Margot Kidder Lois of the big-budget SUPERMAN films displayed a modicum of "street savvy" and gutsiness, but she didn't seem like the sort of reporter who could mix it up with a batch of gun-wielding thugs.

Though 1993's LOIS AND CLARK: THE NEW ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN often played Lois for comic effect, the writers gave her greater efficacy in compensation. Portrayed as the child of an army brat, Teri Hatcher's Lois had a genuine appreciation for the martial arts, as displayed in the Season 2 episode "Chi of Steel." Though she still didn't mow down small armies of thugs, she was frequently seen trading karate chops with assassins or punching out the henchman of the Villain of the Week.

Tuesday, November 6, 2012

YEAR 1992: BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER

Year 1992 should probably get the honorary title of "the Year of the Woman Superhero." It's not that Buffy was the best superhero, or even the best of her horror-oriented subgenre. But in contrast to the live-action flops of SUPERGIRL and SHEENA (both 1984), BUFFY the film was at least a modest success-- which led to the 1997 teleseries.

So what about the original film? Scripter Joss Whedon has said many times that the director wanted it to be more of a comedy than Whedon did. Without my seeing the original Whedon script, I can't judge whether it looks like the director made massive changes. The final shooting script is extremely loose, though, and only rarely does the potential of the concept come across.

It's neither a very funny nor very thrilling film, though Kirsty Swanson (unlike male lead Luke Perry) at least plays the concept relatively straight. In the history of the femmes formidables, BUFFY the movie is essentially an interesting footnote.

Friday, October 26, 2012

YEAR 1991: V.I. WARSHAWSKI

The main point of interest in the film V.I. WARSHAWSKI-- a critical and commercial flop in its day-- is that it might be considered a minor herald of the burgeoning "tough heroine" subgenre that proliferated during this decade.

I haven't read the source-novel by Sara Paretsky, so I can't make an extended comparison. All I remember is that though Kathleen Turner looked great in the role-- garnering what few raves the film got-- the rendition was just another generic Hollywood action-opus, failing to underscore any of the Warshawski character's particular concerns with women's issues.

It does have one kickass scene where Turner's Warshawski has to take a beating from a low-grade thug before she manages to turn the tables on him. Quite a change from the days of the old serials, where heroines almost instantly fainted the first time a bad guy pushed them to the floor.

Saturday, October 20, 2012

YEAR 1990: BREATHLESS MAHONEY

At the risk of pissing off any readers who haven't seen the 1990 Warren Beatty-Madonna DICK TRACY, I'm spoiling the ending: the mysterious masked mastermind known as "the Blank" is none other than Madonna's character Breathless Mahoney.

As noted in my writeup of the comic-strip Breathless, the original character was something less than a high-roller. She's not even a major seductress as per the then-current Madonna personality (not that Chester Gould created a lot of seductress-types). There's nothing much in common between the original and the film-version except the name. It may one of the few times, if not the only time, that a secondary medium improved on not one but two of DICK TRACY's classic villains.

For most of the film, Breathless seems to be one of the typical "bad girls" of film noir, set to tempt the hero-- Dick Tracy in this case-- from his loyalty to a pretty-but-not-glamorous "good girl." Breathless does a pretty good job of keeping Beatty's Tracy "out of breath," but her role in the story seems tangential to Tracy's war on the criminal forces of Big Boy Caprice (Al Pacino) and his many strip-derived allies: Flat Top, Itchy, Prune Face, etc. At the same time Tracy also has to contend with a mysterious blank-faced man trying to take over Caprice's criminal empire. Surprise ending: when it all shakes out, behind the Blank's mask is the face that launched a thousand, uh, fans.

The plot never expands on what motivated Breathless to become a supervillain. However, there is one crucial scene that proves suggestive: after Big Boy takes over the club where Breathless performs, the goony-looking gangster not only takes charge of her career but tries to tell her how to perform as well. That sounds like good enough motivation to turn to crime right there.

I mentioned that the film does two DICK TRACY villains better than the originals, by which I meant that the original Blank, while interesting (and male), is something less than one of the classic Tracy villains.

Wednesday, October 17, 2012

YEAR 1989: THE WOMEN OF THE WOLF

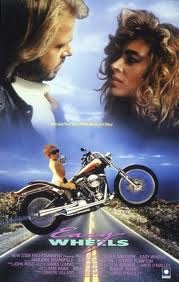

1989 is rather a dub year for femmes formidables, but the comic biker-flick EASY WHEELS deserves to be a bit better-known.

In this deadpan-comic twist on such serious-toned lady-biker films as SHE-DEVILS ON WHEELS and THE MINI-SKIRT MOB, Sam and Ivan Raimi, along with director David O'Malley, introduce the audience to "She-Wolf" (Eileen Davidson), a woman raised by wolves. When she grows to adulthood She-Wolf goes the Pussy Galore route and assembles an all-female biker-gang around her, "The Women of the Wolf." Implicitly they have Lesbian Nation ambitions, for they steal babies after the manner of the archaic Amazons, selling the male babies to illegal adoption agencies and allowing the girl babies to be raised by the wolfpack, as She-Wolf was.

The Wolf-Women have everything going for them until they run across a gang of all-male bikers, whose name, "The Born Losers," contains more truth than poetry. The guys aren't much of a physical threat to the lady bikers, who kick the guys' butts in two separate encounters. Rather, their presence threatens the stability of the group when She-Wolf unintentionally strays from the Isle of Lesbos and falls in love with the Loser-leader Bruce (Paul LeMat).

EASY is pretty tame material, but it sports some nice light-hearted brawls. Sam Raimi would gain greater fame in the Femme Formidable department about six years later when he produced the XENA teleseries.

Wednesday, October 10, 2012

YEAR 1988: THE WHITE WORM

Thus far, this is the only major media adaptation of Bram Stoker's mostly forgotten THE LAIR OF THE WHITE WORM, of which I made brief mention for Year 1911 in THE PREHISTORY OF THE FEMME FORMIDABLE.

Unfortunately, though the Stoker novel is something of a mess, Ken Russell's adaptation is overly jokey and derisive of the source-material. Amanda Donohue makes an appealing enough snake-woman, but that's about all I can remember from this old chestnut. I confess I haven't seen it in about 20 years, however. Perhaps time might prove kinder to the film now.

Sunday, October 7, 2012

YEAR 1987: THE KNIGHT SABERS

As noted elsewhere Japan proved itself a worthy successor to the US in terms of creating iconic femmes formidables. One of the best known femme-centric products of the boom years of the manga/anime juggernaut of the 1980s was the OVA series BUBBLEGUM CRISIS, featuring four female mercenaries known as the Knight Sabers.

As shown above the four women-- Sylia, Priss, Linna, and Nene-- donned body armor in order to fight the destructive androids unleashed upon the MegaTokyo of 2032 by the corrupt Genom corporation. The four women were reasonably well characterized for such a fast-paced sci-fi adventure. CRISIS patterned elements of its future scenario from the film BLADE RUNNER, though a spinoff franchise, A.D POLICE FILES, was much closer to the dramatic tone of the Ridley Scott film.

Sunday, September 30, 2012

YEAR 1986: CARRIE KELLEY

Year 1986 remains most noteworthy in the annals of American comics for having simultaneously introduced two superlative graphic novels: Frank Miller's THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS and the Alan Moore/Dave Gibbons WATCHMEN. WATCHMEN generally enjoys the better critical reputation in the circles of comics-book elitists. But there's one department where the Moore-Gibbons work, with its rather shallow superheroine Silk Spectre, falls short. That's the department of the femme formidable.

In 1986 Miller had yet to start the downward creative spiral that recently culminated in the abysmal HOLY TERROR. He was at the top of his game, and with TDKR he showed protean playfulness in re-inventing the somewhat staid Batman mythos of the time. Arguably the Batman franchise was re-energized across the board thanks to Miller, and the influence of his depiction of his new Robin was a major exemplar of that energy.

To my recollection, up until 1986 no one had ever suggested that it could be desirable that the role of Robin should be essayed by a teenaged female. Today, certain comics-forums are replete with fans who bitterly resent that the character of Stephanie Brown, who briefly essayed the role in a few Batman stories, wasn't chosen to be an ongoing Robin. (She did get to be a new Batgirl for a few months, though.) I suggest that the idea of a female Robin might not have occured to anyone were it not for Miller's take.

Carrie Kelley isn't a particularly deep character, having been designed only for that Miller miniseries. Nevertheless, back when Miller had a great ear for the "voice" of his fantasy-characters, Kelley's voice had the resonance of youth, of eternal innocence born again in the dark world of the Batman. Kelley's Robin wasn't portrayed as especially tough, for she wins her only physical conflict in the miniseries through luck more than skill. Nevertheless, she was a good athlete, and she looked great in the Robin costume, whose splashy colors aren't being donned by the male versions of Robin these days.

I'm not quite so crazy about her later incarnation as "Catgirl" in Miller's follow-up series THE DARK KNIGHT STRIKES AGAIN, so I probably won't cover that here. However, I'll admit that it's a logical development of the original idea, given the dark and perverse nature of the Miller imagination.

Saturday, September 15, 2012

YEAR 1985: FEMFORCE

Americomics' long-running FEMFORCE was not the first comics-feature to present an all-female team of heroes, but it's certainly the longest running, having run over 150 issues. The charter members seen in the illo above include original characters Tara of the Jungle (on the vine), the She-Cat, Ms. Victory, and the Blue Bulleteer, who maintained a dual hero-identity, more often seen as a caped mystic named Nightveil. Of these, Ms. Victory was a revamp of a Golden Age heroine, Miss Victory, published by the long-vanished Holyoke Company. Over the years Ms. Victory and several other members or associates of the team received their own titles, but none had the staying-power of this "Legion of Cheesecake Heroines."

Helmed by writer/publisher Bill Black, Americomics (also called AC Comics) unquestionably evoked the nostalgia of readers familiar with the simple kinetic thrills of early superhero comics. In time Black's company revived a large number of public domain superheroes of the 1940s and 1950s, both male and female, as well as reprinting original adventures of nearly forgotten stars like Catman and the Phantom Lady.

FEMFORCE was never more than a good read, but its penchant for depicting superheroes as light, psychologically unconflicted fun made for a pleasant contrast to the angst-heavy antics of the Big Two during the 1980s and thereafter.

Wednesday, August 29, 2012

YEAR 1984: SUPERGIRL

The debut of Kara Zor-El for the first time in an audiovisual medium may (according to fannish scuttlebutt) have led to the death of the character a year later when DC's CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS came looking for disposable longjohn-types.

The genesis of the film was less than propitious. Without the strong influence of a director like Richard Donner, who molded the superior SUPERMAN films for the Salkind production group, SUPERGIRL feels like nothing more than a telefilm introducing a new series-character. Though director Jeannot Szwarc and scripter David Odell had some decent enough ideas, the execution proved pedestrian and the film itself did not perform well-- thus leading to some fans' suspicions that DC Comics "terminated" the character as part of their 1985 house-cleaning.

On the plus side, Helen Slater delivers a fine performance, combining qualities of innocence and courage in just the needed propotions. Some of the romantic overtones show promise, with Supergirl battling not just to save Earth but also to win her prospective boyfriend from the clutches of an evil Older Woman.

On the minus side, Szwarc begins with a lame premise-- Supergirl goes to Earth hunting for a magical doohickey to keep Argo City alive-- and then lets the action plod around for most of the running-time until finally pulling out some stops for a moderately exciting climax. But by the time one gets there-- after suffering through scenes like one in which the Maid of Might takes ten minutes to dispose of a couple of grabby truckers-- one isn't likely to care much.

Friday, August 24, 2012

YEAR 1983: AMETHYST, PRINCESS OF GEMWORLD

In some ways DC Comics exceeded Marvel in its depiction of femmes formidables in the Golden and Silver Ages, though Marvel's breakout books tended to outshine many of DC's solid but less showy endeavors. In the 1980s, which I for one deem to be the late Bronze Age, DC arguably showed more enthusiasm for featuring heroines in their own features, a trend that seems to continue to this era.

AMETHYST, beginning as a 12-issue "maxi-series" written by Dan Mishkin and Gary Cohn and drawn by Ernie Colon, was a strong attempt to create a fantasy-heroine with enough of a regular "costume" to sustain popularity with the superhero crowd.

In keeping with prose-fantasies like the "Narnia" books of C.S. Lewis, the gateway to a fantastic world is also tied to the central character's desire to mature quickly. On her thirteenth birthday earthbound Amy Winston is kidnapped to an alternate dimension known as Gemworld, where she ages to a young woman of roughly twenty. There she finds out that by birth she is a native princess of Gemworld, that her earthly parents were only adoptive in nature, and that she possesses incredible magic powers with which she can battle the forces of evil menacing her cosmos. At the same time, whenever Amethyst returned to the earth-plane, she immediately regressed to her 13-year-old "secret identity."

Ernie Colon, known for many years as an artist on RICHIE RICH, occasionally allows a few "cartoony" characters in the visuals but on the whole strives to keep an enchanting tone to his depiction of the jewel-obsessed universe. That said, Colon is not an outstanding designer of costumes and creatures, so his execution of Gemworld is pleasing but not outstanding. Cohn and Mishkin are solid craftsmen, but rarely manage to put across anything more than your basic intrigues and skullduggeries.

That said, AMETHYST has been revived on occasion-- which is more than one can say for most of DC Comics' forays into magical fantasy-- and is due for yet another revival in September 2012.

Thursday, August 16, 2012

YEAR 1982: V.I. WARSHAWSKI

Though there had been tough lady detectives in earlier eras, ranging from Bertha Cool in the 1930s to Honey West in the 1950s, many sources credit Sara Paretsky's V.I. (for "Victoria Iphigeia") Warshawski as the first truly feminist detective.

I confess I've only read a smattering of the Paretsky books. I liked the debut adventure, INDEMNITY ONLY, which selectively rewrote the myth of Persephone in feminist terms. Later entries like BURN MARKS and TUNNEL VISION proved less interesting.

Nevertheless, Warshawski-- adept with karate and with a sem-automatic pistol-- certainly qualifies as a "femme formidable." Her style of feminine toughness implicitly stands as a literary response to all the tough-as-nails male private eyes that defined the genre from Sam Spade to Mike Hammer and onward.

The character had one movie adaptation that will discussed separately. Personally, I'd think she'd do better in television, but that's just me.

Labels:

heroine headcount,

v.i. warshawski,

year 1982

Thursday, August 9, 2012

YEAR 1981: ELEKTRA

Technically, Elektra's another character who first appeared in a comic in late 1980, as she first appears in DAREDEVIL #168, dated January 1981. A miss being as good as a mile, though...

Her creator Frank Miller has freely admitted that he patterned Elektra on Will Eisner's lady thief Sand Saref, right down to having his male hero pursue the way of law and justice while his former girlfriend pursued illegal thrills. However, given that the late 1970s began the slow transformation of many juvenile-aimed superhero comics into what I've termed Adult Pulp, Elektra was designed to be a much darker figure than Eisner's jaunty lady thief.

Like Daredevil himself, Elektra's origins are informed by "father issues," in that the death of her father depresses and disillusions her to the extent that her practice of the martial arts is also corrupted. She falls in with one of the baddest of the bad crowds, a sect of murderous ninjas called the Hand. Though in time she breaks away from their order, from them she learns the discipline of being an assassin-- in which identity she falls afoul of Daredevil, a.k.a. her former lover Matt Murdock.

The continuing altercations of Elektra and Daredevil-- as well as other continuing villains Bullseye and Kingpin-- transformed the DAREDEVIL title into a dark tapestry of brutality and sadism, with a few touches of Freudian-themed sex in the mix as well. Finally, in the DAREDEVIL title at least, Elektra transcended the pollution in her soul. However, Miller did not leave the character alone, last reviving for the 1990 graphic novel ELEKTRA LIVES AGAIN.

For some time, Marvel kept the Elektra character sequestered from most of the Marvel universe, apparently in the anticipation that Miller might choose to come back and sell more Elektra books. Eventually, when Miller did not return, Marvel began farming out the character to other raconteurs, much to Miller's dismay.

Wednesday, August 1, 2012

YEAR 1980: STARFIRE AND RAVEN

Both Starfire and Raven make their first appearances in a hype-preview in DC COMICS PRESENTS #26 (Oct 80), leading up to the debut of THE NEW TEEN TITANS title. As most longtime comics-fans will know, NEW TEEN TITANS was one of the most successful titles for DC Comics during a period in which it's often alleged that DC began to make inroads on Marvel's 1970s dominance. Whether this is true or not, it's undeniable that NTT was successful, and much of its success stemmed from its creators Marv Wolfman and George Perez following narrative models supplied both by Marvel Comics generally and THE X-MEN specifically.

Though the revamped X-MEN title of the 1970s would eventually become known for spotlighting a plethora of strong female characters, it must be said that in the original conception the X-group only had one female member, just like the majority of co-ed hero-groups throughout comics history. FWIW, the New Teen Titans started with three female charter members. One was Wonder Girl, a holdover from the last two launches of the title, who will be considered in a separate entry.

Starfire and Raven, in addition to male team-member Cyborg, were all conceived for the TITANS relaunch. And though the two heroines had origins independent of one another, there's a sense in which they reflect opposing female archetypes.

Sigmund Freud is well known for having originated the opposition of the "madonna and the whore," the woman who is set apart from impure sexual matters and the woman who is entirely defined by such matters. Starfire and Raven aren't quite that polarized as sexual archetypes. But I might typify them rather as "the Lusty Wench and the Nun."

Starfire is repeatedly defined, not simply by her sexuality, but by her volatile emotionality. Whether she's fighting an enemy or pursuing a potential lover, the character is defined as going all-out.

Raven is defined by a nun-like sense of restriction, of constantly being hemmed in by her demonic past. Beyond that, Wolfman and Perez chose to give her a power that would constantly challenge her personal boundaries: they made her an empath, always being tortured by her encounters with the extreme emotions of others.

Interestingly, though I don't think Wolfman and Perez ever played Starfire and Raven off one another to any great extent, a 2003 episode of the TEEN TITANS cartoon, entitled "Switched," went to great trouble to stress the contrast between Starfire, who has to pour forth her emotions in order to use certain powers, and Raven, who constantly has to rein in her emotional nature. (The cartoon will receive its own entry as well at some later date.)

Labels:

heroine headcount,

raven,

starfire,

year 1980

Monday, July 23, 2012

YEAR 1979: WILMA AND ARDALA

To date the late 1970s incarnations of comics-originals Wilma Deering and Ardala Valmar are probably the best known today.

Both characters premiered in the 1979 telefilm pilot, BUCK ROGERS IN THE 25TH CENTURY, which managed to secure theatrical release on the basis of the STAR WARS craze.

The lighthearted teleseries never attained any of the deeper resonance of the Lucas conception, but perhaps because Princess Leia was a strong female character, this version of Wilma (portrayed by Erin Gray) was substantially as formidable as the book and comic-strip version. (The Wilma who appeared in the 1939 serial was minimally used, and I haven't seen the one in the 1950 teleseries.) In the telefilm Wilma was first relatively humorless but loosened up in the series proper, to the extent of wearing tight jumpsuits more often than military garb. She didn't get into physical fights as often as the comic-strip version but was in every way treated as a combat-equal.

As noted here the original Ardala was more or less Killer Kane's futuristic gun-moll, though on occasion she attempted to be a world-beater on her own. The teleseries reverses the power between Ardala and Kane, with Ardala upgraded to the princess of a star-spanning conqueror-race-- one loosely based on Buck Rogers' first major foes in the comic strip, a "Yellow Peril"-ish invasion forces called the "Hans" (just a SF-version of "Huns," of course). Kane is merely Ardala's stooge in the teleseries and makes only minor contributions to the storyline. The emphasis is entirely upon Ardala as the would-be mastermind of various plots to both overcome Earth's forces and to seduce Buck Rogers, not necessarily in that order. Ardala commanded far more power than her comic-strip namesake, but in many scripts she loses what claim she has to formidability due to her pettiness and the ease with which Rogers can deceive her. In her last appearance she's pretty much reduced to a basket case by the withering condemnation of an older and more seasoned villainess named Zarina-- who just happened to be played by an older and more seasoned actress known for playing a certain Bat-villainess, Julie Newmar.

Wednesday, July 18, 2012

YEAR 1978: LUM

Though most of the femmes formidables here belong to the mythoi of adventure or drama, Rumiko Takahashi's Lum holds pride of place as one of the formidable females of the comedy mythos.

As I've always recapitulated Lum's origin story here, I won't repeat myself on that subject. It's interesting to observe that she was not initially the star of the series. The first story with Ataru and Lum was followed by a second tale featuring only Ataru and his human girlfriend Shinobu, who encountered another, less science-fictional demon. Then Lum returned in the third URUSEI tale and stayed for the remainder of the series. At a Comic-con in the early 2000s I asked Rumiko Takahashi whether Lum's re-introduction had been intended all along or not, and my recollection is that she said "not": that the original intent was a title focused on Ataru.

Equally oddly, one of her most recognizeable features-- the ability to generate electrical shocks-- doesn't appear in the first Lum story. In the earliest stories her shocking of Ataru is an unintended side-effect of her attempts to show affection, but it quickly progresses to become a science-fictional version of the rolling-pin, the traditional comic means used by wives to chastise their straying husbands.

The early Lum's character is somewhat nastier and more aggressive than later versions. Arguably Takahashi may have diverted some of Lum's aggressions into other characters, such as Benten and Ran. I don't plan to do any entries for the secondary female characters of URUSEI, but suffice to say that Takahashi devotes no small effort to making sure that her breakout series featured plenty of powerful females.

The manga series was successfully adapted to an anime teleseries in 1981, followed by a handful of bigscreen movie adaptations. Since both of these follow the model of the manga-series quite closely, I won't provide entries for any anime-adaptations here.

Monday, July 9, 2012

YEAR 1977: PRINCESS LEIA

There had been tough space-opera females long before STAR WARS, of course, and a few, like THE GOLDEN AMAZON, had their own features. Naturally the mega-success of George Lucas's baby propelled every character in the story into the public's collective unconscious. One might still argue that, both in the film-sequels and in continuations in other media, Luke and Han still tended to get the lion's share of the action. Nevertheless, it's arguable that Leia is far more vital to the mythology than, say, side-characters like Chewbacca and the droids.

Carrie Fisher's sardonic performance does a lot to step up the formidability of Leia in the first film, and it doesn't hurt that (as others before me have commented) that in the battles aboard the Death Star she seems to be the only hero who can hit the targets she's shooting at. She doesn't fare quite as well in THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK, but proves herself to possess more than average fighting-skills in RETURN OF THE JEDI, when she avenges the vile objectification forced upon her by Jabba the Hutt by strangling him to death with her own slave-chain.

As for her appearances in other media, I confess I'm only familiar with her appearances in the long-running Marvel STAR WARS comic. She's generally treated as an equal member of the team with the guys and even gets her own adventures on occasion. (I'd call them "solo" adventures but I'm afraid that might prove confusing.)

Friday, July 6, 2012

YEAR 1976: PHOENIX

In my entry for MARVEL GIRL, I asserted that as originally conceived in 1963, she probably deserved most of the canards hurled at the Invisible Girl and other Silver Age heroines.

In 1976, having written the new X-MEN feature for under a year, writer Chris Claremont and penciller Dave Cockrum formulated a new direction for the character of Jean Grey, to take shape in X-MEN #101. Though in an earlier issue the creators had written Jean's character out of the narrative, they brought her back posthaste in time for the return of the supergroup's old foes the Sentinels. The robotic villains were defeated by the end of issue #100, but the team had to make a speedy exit from a space-station and attempt a landing back on Earth. Jean-- who had not been noteworthy for a lot of gutsy moments in her earlier appearances-- took the job of piloting the craft back to Earth without any shielding from the cosmic rays surrounding the planet, while the rest of her companions were shielded in another compartment. When Cyclops objected to Jean's self-sacrifice, he got the sort of treatment usually given to the hysterial film-female by the tough lead male: she knocked him out, albeit with a mental blast. As seen in the illo above, the superheroes survived the crash, but Jean Grey both died and came back to life as "Phoenix."

Going by the example of the Fantastic Four, one might have expected her to simply become a bigger, badder superhero. Instead, she became a cosmic force, unable to control her desires to do whatever she pleased, despite the peril to sentient races everywhere in the universe. Her tragic fate became the series' primary running plotline for the next couple of years, culminating in X-MEN #137, the end of the so-called "Dark Phoenix Saga."

Death being less than permanent in the Marvel Universe, Jean Grey returned to life later on, and even took on the Phoenix identity in later stories from Grant Morrison, diverging somewhat from official continuity. That said, in effect the original Phoenix as conceived by Claremont and Cockrum never precisely returned, though by a complicated series of incidents she managed to spawn a daughter in an alternate timeline, also called Phoenix, whose most frequent appearances were in the title EXCALIBUR.

Some critics took it amiss that, after Marvel Girl had been a non-starter for many years, she should have ascended to a godlike level of power, only to be summarily destroyed rather than controlling her power and becoming a regular member of the superhero team. However, it should be kept in mind that Marvel Comics had been playing with the concept of "divinization" ever since Lee and Kirby had created Galactus, who was a science-fiction version of omnipotence. Most Marvel characters who didn't begin as gods, but became invested with godlike power at some point, tended to self-destruct in short order, irrespective of their gender. Phoenix should be probably be seen in this tradition.

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

YEAR 1975: STORM

Though the Valkyrie may be viewed as Marvel Comics' first true powerhouse, Storm is the first one to take on mythic properties in terms of her popularity.

Created by Len Wein and Dave Cockrum for GIANT-SIZED X-MEN #1, Storm was one of several new characters designed for the new "international X-Men," one of Marvel's attempts to diverge from the dominantly WASP-y look of most superhero books. Storm possessed formidable powers, able to conjure up great winds, snowstorms, and lightning. Yet her dominant characterization-- that of being regal, yet without pretension-- may have been the quality that most endeared fans to the character. Her original costume by co-creator Dave Cockrum most coalesces both her queenly bearing and her "child of nature" attitude.

It's interesting to speculate whether or not Storm, or other X-Men, would have become as persuasive had Chris Claremont not taken over the series' writing from Wein. Today it's fashionable to sneer at Claremont's stylistic affections, but his passion for the characters-- particularly in terms of giving X-MEN's female characters their unique charisma-- can't be underrated in assessing the success of the series and its protagonists.

Saturday, June 23, 2012

YEAR 1974: WONDER WOMAN

By late 1972 DC Comics had abandoned their experiment with the WONDER WOMAN title, in which the Amazing Amazon lost her super-powers and had to fight evil with the use of mundane martial arts. Thus the super-powered heroine had been back on comics-racks for over a year when ABC-TV debuted the first live-action version of the character.

There had been one earlier attempt to film Wonder Woman as a live-action TV-show pilot in 1967, co-written by Stanley Ralph Ross of the BATMAN teleseries fame. The short pilot, which played the heroine for lowbrow comedy, was never broadcast but has been since been exhumed on sites like You Tube. The 1974 TV-movie WONDER WOMAN, also intended as a pilot for a never-realized teleseries, treated the character seriously but took the same approach as the DC experiment. Thus this incarnation of the heroine (played by former tennis pro Cathy Lee Crosby) was also a former inhabitant of Paradise Island who had left her otherworldly culture behind in order to fight evil in man's world with essentially down-to-earth weapons and abilities. One may speculate that the telemovie's production team (including STAR TREK alumnus John D.F. Black) chose this approach less because of DC's short-lived Wonder Woman experiment but because the mundane approach was cheaper. Crosby did adequately in the role and the telemovie was allegedly a ratings success, but its only effect was to encourage the development of a new series, more in tune with the super-powered heroine as seen in the current comics and the SUPER FRIENDS TV show.

Stanley Ralph Ross was brought in once more, this time for a considerably "straighter" version of Wonder Woman (albeit with more than a few of the farcical touches found in BATMAN); in addition, a new production team, including Douglas "DYNASTY" Cramer, took over the filming of the telemovie pilot THE NEW ORIGINAL WONDER WOMAN. Viewer response for the series was again favorable, so that in 1976 ABC released 11 more episodes of a WONDER WOMAN series (set in the WWII era of the original Marston series). The series' expense discouraged ABC from continuing the project, but CBS picked it up for two more seasons, cutting costs by setting the immortal Amazon's adventures in the present day.

The TV-show's scripts were rarely better than average, and in that respect were far inferior to the original Marston comics. The show's use of FX and fight-choreography was better, but only just. What keeps the show alive for fans today is the perfect casting of statuesque Lynda Carter as Wonder Woman, who embodied the bright-eyed, not-qutie-naive innocence of the juvenile heroine-ideal. As if this writing, no further live-action adaptations of the Amazon have been officially broadcast, though segments of a 2011 David E. Kelley pilot, starring Adrienne Palicki, have surfaced on the Internet.

There had been one earlier attempt to film Wonder Woman as a live-action TV-show pilot in 1967, co-written by Stanley Ralph Ross of the BATMAN teleseries fame. The short pilot, which played the heroine for lowbrow comedy, was never broadcast but has been since been exhumed on sites like You Tube. The 1974 TV-movie WONDER WOMAN, also intended as a pilot for a never-realized teleseries, treated the character seriously but took the same approach as the DC experiment. Thus this incarnation of the heroine (played by former tennis pro Cathy Lee Crosby) was also a former inhabitant of Paradise Island who had left her otherworldly culture behind in order to fight evil in man's world with essentially down-to-earth weapons and abilities. One may speculate that the telemovie's production team (including STAR TREK alumnus John D.F. Black) chose this approach less because of DC's short-lived Wonder Woman experiment but because the mundane approach was cheaper. Crosby did adequately in the role and the telemovie was allegedly a ratings success, but its only effect was to encourage the development of a new series, more in tune with the super-powered heroine as seen in the current comics and the SUPER FRIENDS TV show.

Stanley Ralph Ross was brought in once more, this time for a considerably "straighter" version of Wonder Woman (albeit with more than a few of the farcical touches found in BATMAN); in addition, a new production team, including Douglas "DYNASTY" Cramer, took over the filming of the telemovie pilot THE NEW ORIGINAL WONDER WOMAN. Viewer response for the series was again favorable, so that in 1976 ABC released 11 more episodes of a WONDER WOMAN series (set in the WWII era of the original Marston series). The series' expense discouraged ABC from continuing the project, but CBS picked it up for two more seasons, cutting costs by setting the immortal Amazon's adventures in the present day.

The TV-show's scripts were rarely better than average, and in that respect were far inferior to the original Marston comics. The show's use of FX and fight-choreography was better, but only just. What keeps the show alive for fans today is the perfect casting of statuesque Lynda Carter as Wonder Woman, who embodied the bright-eyed, not-qutie-naive innocence of the juvenile heroine-ideal. As if this writing, no further live-action adaptations of the Amazon have been officially broadcast, though segments of a 2011 David E. Kelley pilot, starring Adrienne Palicki, have surfaced on the Internet.

Wednesday, June 20, 2012

YEAR 1973: COFFY

As I noted in the BUTTERFLY essay, COFFY was Pam Grier's breakout film. Grier's "Coffy" is a nurse who becomes pissed at the drug trade after her brother dies of a drug overdose, so she goes after the gangsters with guns blazing.

Wikipedia relates this behind-the-scenes history:

"According to writer/director Hill, the project began when American International Pictures' head of production, Larry Gordon, lost the rights to the film Cleopatra Jones after making a handshake deal with the producers. Gordon subsequently approached Hill to quickly make a movie about an African American woman's revenge and beat Cleopatra Jones to market. Hill wanted to work with Pam Grier with whom he had worked on The Big Doll House (1971). The film ended up earning more money than Cleopatra Jones and established Grier as an icon of the genre.

Coffy is notable in its depiction of a strong female lead (a capable nurse), something rare in the genre at the time, and also in its then-unfashionable anti-drug message. It was remade in 1981, with an all-white cast, as Lovely But Deadly."

It's certainly interesting, if true, that AIP's COFFY was designed as a response to CLEOPATRA JONES, which was a more expensive-looking production by Warner Brothers, in that Coffy takes the opposite track: emphasizing the squalor and sleaze with which the heroine must contend. By comparison, federal agent Cleopatra Jones, as essayed by model Tamara Dobson, conveys a sense of being "above" all the drug-trafficking she battles. Coffy seems a more "everywoman" hero, particularly in the racial conflict conveyed by the film's end scene. For this reason she may have been acquired a broader appeal with a variety of audiences, though to be sure her period of action-film stardom ended when the "blaxploitation" craze petered out. Nevertheless, Grier remained an icon and, unlike Dobson, continues to work in films and television to the present day.

The Wikipedia excerpt has three problems. As I noted earlier, Grier isn't an especially significant character in 1971's BIG DOLL HOUSE, but she was one of the stars of 1972's BIG BIRD CAGE (also by Jack Hill). I suspect that film, not DOLL HOUSE, was a likely influence on the producers' deciding to give Grier an even more central role for COFFY.

In addition, while COFFY would seem to be the first femme-formidable within the blaxploitation genre, she wasn't the first of her kind, even in American cinema. Two films that may have influenced COFFY's rise to fame were 1971's GINGER, in which blonde Cheri Caffaro works with the government to expose a drug/prostitution ring, and 1972's HANNIE CAULDER, in which Raquel Welch takes up arms to avenge her rape by three outlaws.

Lastly, I've seen LOVELY BUT DEADLY, and I don't think it's a remake of COFFY. At most DEADLY might've swiped the basic plot of the "anti-drug crusader," but nothing else resembles the 1973 classic.

Labels:

coffy,

funners,

heroine headcount,

year 1973

Sunday, June 17, 2012

YEAR 1972: LADY SNOWBLOOD

One of the more noteworthy femmes formidables of 1970s manga was the righteous assassin Lady Snowblood, who sometimes went after her (evil) targets with complicated schemes but who could also devastate any number of men with her superlative sword-skills.

Created by writer Kazuo Koike and artist Kazuo Kamimura for the manga magazine WEEKLY PLAYBOY, Snowblood's adventures have much of the same emotional rigor one finds in Koike's samurai epic, LONE WOLF AND CUB. I devoted a myth-analysis of one Lady Snowblood story.

One year later a film starring Meiko Kaji portrayed Snowblood's origin, with a sequel following the next year. Quentin Tarantino's KILL BILL pays homage to several scenes in the first SNOWBLOOD, as extensively analyzed in this REMARKABLE blogpost.

Labels:

heroine headcount,

lady snowblood,

year 1972

Wednesday, June 13, 2012

YEAR 1971: THE BUTTERFLY

Although Marvel's Storm remains the best-known black superheroine, the first one appeared in a backup strip in HELL RIDER #1, one of a handful of black-and-white comic-magazines from Skywald Publications, which took its name from publishers Sol Brodsky and Israel Waldman. Brodsky, formerly the production manager for Marvel Comics, would seem to have been most responsible for the feel of the HELL RIDER magazine, which was that of regular Marvel superheroes infused with the mildly transgressive sex and violence possible for the non-Code b&w magazines.

The Butterfly appeared in two backup strips in the two issues of HELL RIDER, as well as participating in a crossover between her, the titular Hell Rider, and the magazine's third feature, "The Wild Bunch." The Butterfly was never given a formal origin, but was simply presented as singer Marian Michaels, who fights crime in a costume that includes a jet pack to give her flight and wings that radiate light to blind evildoers.

The Butterfly almost certainly takes her cue from the growth of "blaxploitation" cinema in the late 1960s and early 1970s, though Skywald was slightly ahead of the curve purely in respect to creating a memorable black femme formidable. Not until 1973 would cinema come out with two vehicles for black action-heroines, Pam Grier's COFFY and Tamara Dobson's CLEOPATRA JONES. To be sure, Pam Grier made two appearances as a formidable femme in two 1971 WIP films-- WOMEN IN CAGES and THE BIG DOLL HOUSE-- but she isn't the star of either production, and it seems unlikely that the Skywald creators had her on their minds when they created the first black costumed heroine.

Thursday, June 7, 2012

YEAR 1970: THE VALKYRIE

Though I don't agree with critics who dismiss Marvel's 1960s superheroines as wimps, I've admitted in some of my ARCHETYPAL ARCHIVE essays (such as this one) that the Valkyrie was one of the few heroines whose power was close to the level of Marvel's "big guns" like Hulk, Sub-Mariner etc. But as I noted in the above cited essay, the Valkyrie begins life as a put-up-job: as an alter ego for the evil Enchantress (another one for whom I've not yet done an entry). Much later, an incredibly convoluted J.M.de Matteis story would establish that the image conjured up by the villainess was that of a real Asgardian warrior-maiden, so in a retcon sense, AVENGERS #83 in 1970 is indeed the first apperance of the Valkyrie's image, if not her essence.

The essence would appear about a year later, in INCREDIBLE HULK #142. I critiqued this story in this essay, which was originally intended to be part of a full-fledged examination of the character's myth-history. I lost interest at some point, but the HULK story remains the first time the Valkyrie takes on a decisive persona, even if it would take the aforesaid retcon to establish that she was more than just the Enchantress' spell overlaying a mortal persona.

As most Marvel readers know, the most-used version of the Valkyrie would appear about two years later, with the Valkyrie persona overlaying yet another mortal bit-player in DEFENDERS #4.

Labels:

heroine headcount,

the valkyrie (marvel),

year 1970

Thursday, May 31, 2012

YEAR 1969: VAMPIRELLA

As the sixties drew to a close the publishers of "mainstream" color comics were still hemmed in by their self-policing Comics Code. However, for roughly five years Warren Publishing had been bypassing the restrictions of the Code with his black-and-white horror-comics magazines, CREEPY and EERIE, and no new anti-comics jeremiads were mounted against him. In Sept 1969 Warren published the first issue of another b&w magazine, entitled VAMPIRELLA, created by horror-magazine icon Forrest J. Ackerman and artist Trina Robbins.

In early issues Vampirella-- an alien vampire from the planet Drakulon-- functioned much as did the horror-hosts of CREEPY and EERIE, serving as a "mistress of ceremonies" for an assortment of horror tales. However, within a few months Vampirella became the star of her own horror-adventure stories, as she journeyed about the planet Earth, seeking to overthrow evil devil-cults and find romance at the same time.

Patently Vampirella's costume-- probably the most revealing to debut in the 1960s-- had a "Playboy Club" aesthetic behind it. That said, Vampirella was not reduced to an object by her skimpy attire. She had a wealth of vampiric powers, including super-strength, hypnotism and the ability to grow batwings and fly.

An excellent essay on Vampirella's costume and one of her foremost artists, Jose Gonzales, can found at

The Groovy Age of Horror.

YEAR 1968: TARA KING

By 1968 the British teleseries THE AVENGERS had lost the services of Diana Rigg to portray the popular character of Emma Peel. For the serial's next (and, as it turned out, final) season, the producers cast Linda Thorson as John Steed's new partner. Whereas all of Steed's other partners for the entirety of the series had been "talented amateurs," King was introduced as a spy who had gone through the same training as Steed, and worked for the same barely defined secret organization.

In the circles of television fandom, many viewers disdained Thorson's character not for its own failings but simply for not being Emma Peel. It's questionable whether or not the series would have done any better, aesthetically or financially, had the producers attempted to follow the model set by Peel and the previous Cathy Gale figures.

Whereas the tone of the Gale and Peel seasons captured a fine balance of drama and tongue-in-cheek humor, the final season with Tara King (1968-69) fumbled, occasionally straying into the realm of farce (particularly in those episodes that dealt with Steed and King's supervisor, a fat man known as "Mother.") Being a more petite woman Thorson was not quite as impressive in fight-scenes as Blackman and Rigg had proven, but of the 33 episodes completed there are probably a good half-dozen battles in which King acquits herself just as well as her predecessors.

Tara King made her first prose appearance in 1968's THE DROWNED QUEEN by Keith Laumer, one of four paperback originals. Amusingly, sometimes Emma Peel was featured on the cover of a Tara King adventure.

Saturday, May 26, 2012

YEAR 1967: BATGIRL

Although in some reminiscences Julie Scwhartz claimed that he didn't even remember the Bat-Girl of the Jack Schiff period, I find it interesting that the above cover-copy emphasizes a "new Batgirl," suggesting that someone in the organization did remember the previous version (who'll get a separate writeup at some future date).

Despite all other versions to take the Batgirl name, the Barbara Gordon version remains the best-known one to the general public thanks to her appearances on the live-action television series. Indeed, the Gordon version seems to have evolved in response to a demand from the TV producers, according to a reminiscence from Carmine Infantino:

" Batgirl came up in the mid-’60s. The “Batman” TV producer called Julie and said Catwoman was a hit, could we come up with more female characters? Julie called me and asked me to do that. I came up with Batgirl, Poison Ivy and one I called the Grey Fox, which Julie didn’t like as much." The show's producers liked the Batgirl concept and introduced the character in the third and final season of BATMAN. The character in the teleseries was understandably somewhat jokier in tone, but was still admirable in terms of her ability to defend herself from assorted vile villains.

So well known is the character that I won't go into her specific history and abilities here. I will note that though the Gordon Bargirl was a dynamic and charismatic figure in comparison to the BATMAN series' previous distaff knock-offs, that charisma became dissipated when she gained a semi-regular berth of a backup series in DETECTIVE COMICS. Some of these stories were decent enough formula, but over time they became less and less memorable, and so did the character. A period when Barbara Gordon became a senator, however laudable as an idea, failed to ignite fannish enthusiasm for the character.

Ironically, Alan Moore's use of Gordon as a throwaway victim in the graphic novel THE KILLING JOKE proved the best thing that could have happened to Barbara Gordon in terms of making her popular with a new fan-base-- though of course the credit for rethinking her as "Oracle" goes to Kim Yale and John Ostrander. Oracle will receive a separate writeup.

At present, DC's "new 52" features the Gordon Batgirl in a new series which does seem to fulfill much of the potential that was wasted in the 1970s.

A quick aside about dates: comic books are the only media whose publication dates are unreliable, in that they're generally dated three months ahead of their actual appearance. Thus the "1967" date on DETECTIVE COMICS #359 is inaccurate, in that the magazine actually appeared on newstands in Nov 1966. However, because I can't be entirely sure that everything is dependably dated exactly three months ahead-- so that a comic with a March date might be either December of one year or January of another-- I've decided to continue dating characters' comic-book apperances by their somewhat unreliable publication dates.

Sunday, May 20, 2012

YEAR 1966: THE CATWOMAN

Prior to the 1966-68 teleseries, Catwoman, like the rest of Batman's classic villains, had never been translated to audiovisual media. For its first season, the BATMAN producers seemed incapable of making a bad casting-choice-- though they'd make up for it by going in the opposite direction in the following two seasons.

Like the other villains introduced in the first season, this version of Catwoman is a ruthless career criminal, capable of double-crossing a hireling at a moment's notice. Unlike the comics-Catwoman, the villainess appears more than willing to kill the Dynamic Duo on several occasions. She becomes a little more merciful in the second season, when the writers incorporate her frustrated desire for Batman, and on occasion she merely tries to reduce the Crusaders to helpless slaves rather than killing them. Nevertheless, even the more merciful death-traps have a strong sadistic vibe.

Strangely, though Julie Newmar only played the role once in the Spring 1966 season, the version of Catwoman that appears in the big-screen BATMAN movie-- quickly filmed in the summer to take advantage of the teleseries' mammoth popularity-- seems a much less formidable character-- perhaps making it fitting that she's played by another actress, Lee Meriwether. In all likelihood this bush-league Catwoman came about because the scripter chose to focus on the evildoing of her three male partners-- Joker, Riddler, and Penguin. Still, she seems to possess so little supervillain-moxie that one wonders why she's even in the group. Her only skill appears to be her ability to pull off a masquerade as a Russian journalist, which seems to have no great relevance to the villains' overall scheme. That scheme rested on the improbability that the Batman in this filmic universe had never seen the Princess of Plunder unmasked, but I doubt that the scripter was even thinking of continuity here.

In the second season Newmar returned to the character and she takes on a much stronger persona once more, in spite of being played for more romance and more humor. Like the TV-Batman she makes a lot more use of super-scientific gadgets than the comic-book character had up to that point, but resembles the comic-book version in that neither possessed any martial abilities.

Newmar was perhaps wise not to play the character in the third and last season. The character was played with some aplomb by Eartha Kitt, though the plots had become silly and threadbare.

During this period Catwoman made her first prose appearances, in an original novel-- BATMAN VS. THE THREE VILLAINS OF DOOM-- and in a novelization of the film, retitled BATMAN VS. THE FEARSOME FOURSOME, both credited to one "Winston Lyon." Interestingly, THREE VILLAINS describes Catwoman's costume along the lines of her classic green-and-purple togs.

Thursday, May 17, 2012

YEAR 1965: EMMA PEEL

Though Cathy Gale hit the airwaves first, Emma Peel became the femme formidable most associated with the AVENGERS franchise.

In the Cathy Gale entry, I wondered whether or not Honor Blackman's take on the tough-girl character might have been just as popular as Diana Rigg's. On consideration I would say no, in that Blackman had conceived her character largely as a no-nonsense sort of character, for all that she was an amateur. Rigg, playing the same kind of amateur spy caught in John Steed's weird world of espionage, projects the "aint' foolin' around" air whenever necessary, but in calmer moments puts across a charming insouciance, such as one sees in the shot above, taken from the iconic AVENGERS theme/opening.

More than a few female fans have cited Emma Peel as one of their earliest images of a "strong heroine," not least because of the character's penchant for doling out karate chops and judo throws. She did on occasion lose a fight, but no more than her partner Steed did. As series-fans know, Rigg and Patrick Macnee managed to keep viewer interest high by injecting a frequent "are they or aren't they" chemistry, one that fortunately never becomes sappy as in similar American attempts.

Two years later, Emma Peel appeared in one of five paperbacks. This Emma tended to be somewhat more sardonic and ruthless than the light-hearted TV version..

Three years later-- by which time Diana Rigg had left the AVENGERS teleseries-- Emma Peel made her first comic book appearance from the company Gold Key. Because of a certain heavyweight competitor, the one issue published was not titled THE AVENGERS but rather JOHN STEED AND EMMA PEEL.

Tuesday, May 15, 2012

YEAR 1964: THE BLACK WIDOW

It's at least an interesting turnabout that a character originally intended as a stock stereotypical threat-- in this case, that of a nasty Commie spy-- should eventually become one of Marvel Comics' most respected heroines.

When the Black Widow first appears in TALES OF SUSPENSE #52, her only superpower was her mysterioso hotness.

Garbed in this Natasha Fatale getup she unsurprisingly pulls the wool over Tony Stark not once but twice, but both times she's ultimately thwarted by Iron Man.

Since Lee and/or one of his collaborators had given her a super-person sort of name, though-- one that even suggested a "Black Widow" who'd been published by Marvel's ancestor Timely in the 1940s-- it probably posed no great leap of logic for Stan and Co. to rethink her as a costumed supervillain with artificially-created spider-powers. Strangely, though it wouldn't be unusual to think of a former spy as possessing martial arts abilities, during the 1960s the new Black Widow was never seen dishing out kicks or karate chops, depending almost entirely on her weapons-system, her "widow's bite" wrist-zapper.

In AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #86 (dated July 1970), her costume was remodeled into its best-known version-- a slick one-piece black leotard-- and she became a practitioner of extraordinary martial arts. The SPIDER-MAN guest-appearance was co-ordinated as a lead-in to her series in AMAZING ADVENTURES, but though that series proved short-lived, the Widow continued to get regular exposure in Marvel Comics through her co-starring appearances in DAREDEVIL and her eventual (though much-delayed) membership in THE AVENGERS.

When the Black Widow first appears in TALES OF SUSPENSE #52, her only superpower was her mysterioso hotness.

Garbed in this Natasha Fatale getup she unsurprisingly pulls the wool over Tony Stark not once but twice, but both times she's ultimately thwarted by Iron Man.

Since Lee and/or one of his collaborators had given her a super-person sort of name, though-- one that even suggested a "Black Widow" who'd been published by Marvel's ancestor Timely in the 1940s-- it probably posed no great leap of logic for Stan and Co. to rethink her as a costumed supervillain with artificially-created spider-powers. Strangely, though it wouldn't be unusual to think of a former spy as possessing martial arts abilities, during the 1960s the new Black Widow was never seen dishing out kicks or karate chops, depending almost entirely on her weapons-system, her "widow's bite" wrist-zapper.

In AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #86 (dated July 1970), her costume was remodeled into its best-known version-- a slick one-piece black leotard-- and she became a practitioner of extraordinary martial arts. The SPIDER-MAN guest-appearance was co-ordinated as a lead-in to her series in AMAZING ADVENTURES, but though that series proved short-lived, the Widow continued to get regular exposure in Marvel Comics through her co-starring appearances in DAREDEVIL and her eventual (though much-delayed) membership in THE AVENGERS.

Labels:

black widow (marvel),

heroine headcount,

year 1964

Sunday, May 13, 2012

YEAR 1963: MARVEL GIRL

Critics like Trina Robbins and Alan Moore have been unjust to the Invisible Girl, implying that all there was to her were her stereotypical "girly-girl" traits, ignoring her genuine gutsy moments. This is particularly egregious in that just two years later Marvel created a female who was guilty of most if not all of the canards directed at Sue Storm.

The most one could say of the early Jean "Marvel Girl" Grey was that she was courageous in a somewhat stereotypical manner. But where Sue Storm often came off as having a certain amount of grit beneath her femininity, Jean Grey was largely a blank slate as created by Lee and Kirby in X-MEN #1 (Sept 1963). Her telekinetic power was rarely of much use in early stories, though admittedly by the late 1960s she became more adept with other psychic talents, such as mind reading and psychic attacks.

Her humble powers, however, were less injurious to her persona than the fact that her Silver Age raconteurs-- including those who followed Lee and Kirby-- used her as nothing but "the girl whom the team-leader loves." X-Men storylines brooded over the difficulties of the group-leader Cyclops as he morosely forbade himself to date Jean, thus almost throwing her into the arms of competitors like Warren "the Angel" Worthington and Cal "the Mimic" Rankin. But there was scarcely anything in the stories about Jean's personality. Modern fangrils may not like the personalities of the Invisible Girl or the Wasp, but at least the characters had definite (for pop culture) personas. The character of Jean Grey went to college, but as I recall the stories never even alluded to what she majored in, or when she dropped classes. To be sure, the FANTASTIC FOUR's Human Torch had a similar abortive college career, but at least he had some valid experiences of his own at college, rather than being someone else's love-object.

Curiously, Jean Grey and the rest of the X-Men made one appearance in the medium of television in 1966, when an episode of THE SUB-MARINER tossed together various scenes from a couple of FANTASTIC FOUR stories into a strange amalgam, with the X-Men being re-christened "the Peace Alliance."

Some years after the cancellation of the first X-MEN series, some creators meditated on the possibility of refurbishing Marvel Girl as a new kickass superheroine called "Ms. Marvel," but in the final version support-character Carol Danvers received the superheroic makeover instead. However, when the X-MEN received its second and most famous relaunch in 1976, within a few years Chris Claremont and Dave Cockrum chose to give Marvel Girl an even more radical remodeling as "Phoenix," who will receive her own separate entry.

For some reason, the name "Marvel Girl" wasn't even used for the 1990s X-MEN teleseries, which billed the character as simply "Jean Grey."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

_)001.jpg)