Wednesday, February 29, 2012

YEAR 1942: IRENA DUBROVNA

Femmes formidables in 1942 aren't quite as numerous as in '41, but the superhero comics-boom still showed some strong contenders. However, as I want to keep some focus on other media, I'll focus first on one of the first "female monsters" to appear in sound cinema: the "cat woman" Irena Dubrovna.

I confess I'm not a huge fan of 1942's CAT PEOPLE, with its "did she did or did she didn't turn into a panther" schtick. This suggestive approach to the horror genre is perfectly fine for those who like it, but I tend to prefer a less ambiguous approach myself.

That said, though the viewer can never be absolutely sure whether or not Irena's transformations are the result of a disturbed mind tormented by jealousy and the crassness of American culture, Simone Simon's performance as Irena at least makes it possible for one to see her as the inheritor of the strange power of "the cat people." In that respect at least, Irena does display the power of a femme formidable.

Saturday, February 25, 2012

YEAR 1941 : WONDER WOMAN

1941's actually a pretty good year for femmes formidables, but there's no question that WONDER WOMAN rises to the top of the heap.

Though she was not the first costumed superheroine-- even if one disincluded types like SHEENA and FANTOMAH-- she seems to have been the first coherent "femme formidable" response to Superman. Her original name in William Moulton Marston's proposal was "Suprema," which sounds fairly close to the name of the Siegel-Schuster creation, while two years later Marston remarked upon the resemblance in an issue of THE AMERICAN SCHOLAR:

Not even girls want to be girls so long as our feminine archetype lacks force, strength, and power. Not wanting to be girls, they don't want to be tender, submissive, peace-loving as good women are. Women's strong qualities have become despised because of their weakness. The obvious remedy is to create a feminine character with all the strength of Superman plus all the allure of a good and beautiful woman.

Patently Wonder Woman did allow Marston to elucidate a concept of woman as a "best of all possible female characteristics," allowing her to show evidence of tenderness and what Marston often calls "lovingkindness" even when she's also demonstrating "force, strength and power." This might be a very loose critique of the "tough guy" ethic embodied by the early Superman and most of his imitators. Since Marston was executing an adventure comic book aimed at children, he must have known that most of them would be drawn to the selling-point of amazing feats of power. What distinguishes Marston's hero from most others is that Marston's scripts (quirkily but winningly executed by artist Harry G. Peter) consistently emphasize the need to build a new society of equals following the defeat of the forces of evil.

Marston's conceptualiztion of the Amazon's "dominance-and-submission" society has been the topic of much heated discussion on contemporary message boards. It's easy to poke holes in many of Marston's concepts, but whatever its failings, WONDER WOMAN stands as the first American comic book to evince any sort of philosophical stance. Even comic books and comic strips which critics judge to be superior in terms of script and art (such as Will Eisner's SPIRIT) usually have no philosophical underpinnings as such.

One small hole I can't resist poking myself is that despite all of the Amazon's lip-service to the nobility of submission, Wonder Woman isn't often seen in a submissive posture. Occasionally she's put in bondage and makes some mental comment about enjoying it, but my perception of the emotional appeal of bondage (speaking as an outsider) is that one *can't* get out of it; that one has to make some mental adjustment in order to submit with grace. Largely Wonder Woman doesn't walk her own walk; it's always someone ELSE who has to submit, not her.

That said, Marston's insight into the interdependence of those qualities that Socrates called "valor" and "temperance" is little short of inspired. In an ARCHETYPAL ARCHIVE essay I wrote:

The action-heroine is a better symbol of the Schopenhaurean Will than the male action-hero.

If I had to choose a particular heroine to embody that symbol, no other would be even close.

Labels:

fibbers,

heroine headcount,

wonder woman,

year 1941

Wednesday, February 8, 2012

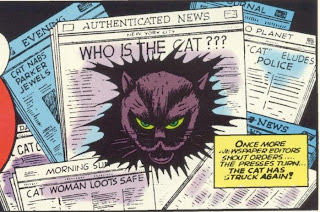

YEAR 1940: THE CATWOMAN

Given that someone else already thought of doing the "nine lives" schtick with the nine (or more) costumes of the character's existence thus far, I'll attempt something more original: nine symbolically significant aspects of Catwoman's career.

(1) IN HER VERY FIRST ADVENTURE, INTREPID CRIMEFIGHTER BATMAN LETS "THE CAT" GET OUT OF "THE BAG"

Whereas the ordinary thugs and grifters of Batman's world were generally exposed as cowards and losers, the costumed criminals never suffered a lot of sanctimonious preachments. Possibly this was because the audience knew that they were not naturalistic, and so could take vicarious pleasure in their acts of robbery and murder. Catwoman (a.k.a. "The Cat") was probably the most liberating of these figures once the writers made it a cardinal rule that she always avoided taking human life during her robberies; thus her thefts became more like a game with no consequences for anyone but the insurance companies. Of course Batman's motive for releasing this "shady lady" back in BATMAN #1 have more to do with wanting to "bump into her again sometime." Not that there's anything wrong with that.

(2) CATWOMAN'S AMONG THE FIRST, IF NOT THE FIRST BAT-FOE, TO WEAR A REAL COSTUME

To be sure, the first costume the demi-villainess sported, back in BATMAN #1-- a big cat-mask over her head, while the rest of her wears either a gown or a foofy caped outfit-- is an awful costume. But most of Batman's foes-- Joker, Penguin-- simply wore slightly outre versions of regular clothes. Later, once Catwoman donned her classic purple-and-green togs, she also began biting Batman's style in other ways, using "cats" as fetishistically as he used "bats." If Batman had a Batarang, she had a cat-o-nine-tails; if he had a Batmobile, she had a Kitty-Car, etc. During BATMAN YEAR ONE Frank Miller posited that the early Batman's example inspired the Princess of Plunder to follow that example on behalf of crime, which was, all things considered, one of Miller's better insights into the Bat-cast.

(3) THE NAME "SELINA KYLE"

The name "Selina" is patently a derivation from the name of the Greek goddess of the moon. There's no textual indication in the early adventures that the writers went out of the way to emphasize any "lunar" aspect of her nature or her adventures, so the symbolic meaning of the character's given name may merely be happy coincidence. In any case it fits, in that "cat" and "moon" tend to symbolize mysterioso qualities. A Catwoman named "Sunny Kyle" just wouldn't have been the same.

(4) THE CLAWS

The above scene, with Catwoman clawing the hell out of a nine-year-old boy sidekick's shoulder, appears nowhere in the actual story. By the 1940s the idea of women defending themselves by clawing at men with their long nails was a routine trope, but the cat-gimmick does make it seem less a last-ditch defense and more like an assertion of essentially feminine power.

(5) THE CAT-O-NINE-TAILS

Yes, whip it, whip it good-- ah, Catwoman and her whip. Its presence inspired scenes like the DETECTIVE COMICS scene above: since it resembles nothing in the actual Catwoman story within, clearly it inspired some artist to new heights of, shall we say, "inspiration." The presence of the whip also excited the wrath of Frederic Wertham. Catwoman may not be the only costumed villain named in SEDUCTION OF THE INNOCENT, but she's the only villain from Batman's rogues gallery who's honored as being a corrupter of innocent youths.

(6) THE CAT DIDN'T COME BACK (UNTIL 12 YEARS LATER)

Between 1954, when "The Jungle Cat-Queen" appeared in DETECTIVE #211, and 1966, when the Catwoman appeared in (of all things) a LOIS LANE story, the Catwoman was effectively exiled from DC Comics. To be sure, no DC employee has ever spoken of a freeze-out. But given that Batman's editor Jack Schiff kept bringing back vintage Batman foes like Joker and Penguin during that period, I believe DC was skittish about the character thanks to the bad publicity they got from Dr. Wertham over her. In 1963 DC evidently thought the cat-gimmick too good to waste, so writer Bill Finger created a feline-themed villain, the Cat-Man, who explicitly thought he could be a better cat-villain than Catwoman simply because he was a man. In addition, this Cat-Man even tried to convince Batman's female ally Batwoman to become a new "Catwoman," but she only went through with the whole megillah to twist the villain's tail, so to speak.

(7) PRINCESS OF BUZZKILL

Michael Fleischer was somewhat over-Freudian when he declared, in the BATMAN ENCYCLOPEDIA, that Catwoman was to Batman an image of his departed (and therefore "bad") mother. However, early adventures do evince a sense that Robin's often threatened by Batman's feelings for the cat-crook, but not for the puerile reasons Frederic Wertham cited. Rather, Robin's got a perfect life from a nine-year-old's perspective-- a good older guardian who lets him stay up late and fight criminals. Catwoman is definitely a "bad mother" to him in that her erotic presence threatens to steal the Caped Crusader away from the manly art of crimefighting.

(8) KAT-RATE

The one aspect of Batman that Catwoman didn't imitate for her first 20 years was that she couldn't fight; at best she occasionally managed to catch the hero off guard with some roughhouse maneuver. Apart from her skill with the whip she wasn't seen as a physical threat. To be sure, though costumed heroines were often mistresses of judo and boxing, villainesses of the 1940s and 1950s rarely showed such traits, and Catwoman *was* the only memorable female villain of the Batman comic books until the middle 1960s, when Poison Ivy debuted. However, once Catwoman's skills were mysteriously upgraded in the early 1970s, most of the other larcenous ladies followed suit in one way or another. Still, it's a shame that Catwoman was relegated to being a "weak sister" during most of Batman's Silver Age, when heroines like Batwoman and the original Bat-Girl were shown tossing their enemies hither and yon.

(9) JULIE NEWMAR

Self-explanatory.

Labels:

catwoman,

funners,

heroine headcount,

year 1940

Friday, February 3, 2012

YEAR 1939: THE GOLDEN AMAZON

I have little direct experience with the actual stories of The Golden Amazon, a character who first appeared in the July 1939 issue of FANTASTIC ADVENTURES and who enjoyed three more stories there. Of those four adventures of the Amazon-- said by some to be a possible influence on Wonder Woman-- I've read only the third, "The Golden Amazon Returns," which sums up her origin thusly:

"The only survivor of a space wreck on Venus, she had been found as a baby by Venusian Hotlanders. They had taken care of her, and the child had matured in the environment of Venus..."

And later, due to the way she was bombarded by the sun's rays coming through Venus' cloud-cover:

"Instrad of human cells breaking down, they had built up to ever increasing toughness."

This has a slight resonance to one of William Moulton Marston's explanations for the fabulous strength of his Amazons, which had to do with their directing pure "force of will" into their muscles.

"Golden Amazon Returns" seems to be characteristic of the series, focusing on slam-bang action. The Amazon, whose winsome civilian name is "Violet Ray," isn't quite as superhuman as Wonder Woman-- at one point four men manage to restrain her-- but she's more than a match for any man in a punching contest.

In 1944 the Amazon's creator, British writer John Russell Fearn, "rebooted" the character for an original novel. To my knowledge she had no other media-incarnations until the 1980s, which I'll cover in a separate post.

Labels:

heroine headcount,

the golden amazon,

Year 1939

Thursday, February 2, 2012

YEAR 1938: LOIS LANE

Like Wilma Deering, Lois Lane is best known through association with a top-billed male hero, though I do consider Wilma to be a valid sidekick to Buck Rogers, whereas in the Golden Age SUPERMAN comics, Lois is more like "support-cast." Nevertheless, she is arguably the most integral part of the Superman mythos aside from the hero himself, in that Superman's debut story, which appears serialized in ACTION COMICS #1 and 2, keeps a strong focus on the strange relationship (Jules Feiffer called it "masochistic") between Lois, Superman and Clark Kent.

Regrettably, many comics-fans view Lois Lane through the lens of the Silver Age comics: as a harebrained schemer who was always trying to force Superman to marry her. The Lois Lane created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster had her flaws-- a hard-bitten nature, foolhardiness-- but she wasn't usually stupid, as she all too often was in the Silver Age. In addition, she was pretty courageous, willing to pop a hoodlum in the mouth if she got the chance-- though she did end up being the "damsel in distress" in most adventures. She briefly became a "Superwoman" for one adventure, and fannish rumor has it that perhaps DC considered spinning her off as a full-time heroine, but during the Golden Age she only received a brief backup series, largely comic in tone.

The Silver Age LOIS LANE stories have their merits, but the most interesting aspect for this blog is that in the late 1960s Lois finally gets some heroic chops and starts fighting with karate-style moves. Most later depictions give her this badass skill, though clearly she's not meant to be in the same league with real kickass heroines.

Wednesday, February 1, 2012

YEAR 1937 : SHEENA

In THE PREHISTORY OF THE FEMME FORMIDABLE IN POP CULTURE, I wrote:

Wilma’s prose advent marks a turning point in the development of the pop-cultural archetype of the femme formidable: the “fighting femme formidable.” I don’t suppose that Wilma was the first of her kind, but she seems to be the first to have garnered some measure of lasting fame...

Wilma Deering was the first woman who was portrayed as consistently kickass, though usually she fought with a gun rather than fists and feet. However, the first kickass female with her own series who PRIMARILY depended on her physical skills was certainly Sheena, Queen of the Jungle. She debuted in 1937, about a year before the appearance of Superman, in the first issue of the British tabloid WAGS. The character's debut story was then reprinted in the first issue of the American comic book JUMBO COMICS, about three or four months after Superman showed his cape in ACTION COMICS #1. Her general history is aptly covered in this online essay.

The character's genesis has been credited (though this has been disputed) to the comics-team who packaged the material for WAGS and for many American comics thereafter: Will Eisner and J.M. Iger. Thematically, Eisner does seem like a likely creator, since his SPIRIT series hosts dozens of tantalizing femmes formidables. However, most of his own works emphasize male characters as the stars, so it may be that his influence in launching the strip was largely as a facillitator. The basic concept of the series seems to owe something not just to Tarzan but to the 1931 film TRADER HORN, which featued a white woman raised to be the queen of a black African tribe.

Many have claimed that the main reason for Sheena's popularity was her extreme hotness as she ran around the jungle beating up unruly natives. There's no way this can be proven or disproven, but the Sheena stories were also better drawn and written, in terms of pulp virtues, than an awful lot of product in that period. Thanks to her media-adaptations, the first female "superhero" remains reasonably well known long after her comic book's demise.

Labels:

fibbers,

heroine headcount,

jungle gallery,

sheena,

year 1937

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)